FFRF has helped people remove this language from diplomas and other government documents, usually because they were willing to complain openly and point out that the use of this language in the date is completely unnecessary, and alienates many citizens.

Some institutions may offer an alternative. For example, attorneys seeking admission to the U.S. Supreme Court are able to choose whether they want the “Year of our Lord” date on their admission certificate or the traditional date. Upon application, attorneys are able to indicate their preference for the certificate. Thus, if you don’t want it on your diploma, tell your school. If you don’t want it on your government document, complain. The more institutions hear complaints about having religious wording on secular documents, the more likely they are to change the practice.

There is a second, more insidious face to the phrase. These four words—”Year of our Lord”—are occasionally used to argue that the Constitution is somehow a Christian document. This argument is fallacious.

Is the date even part of the Constitution?

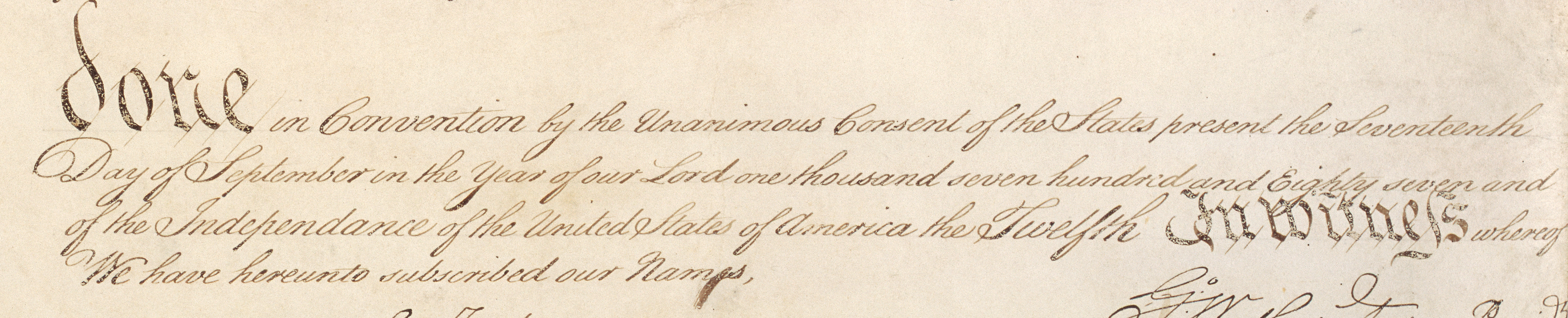

Here’s a photo of the final words, know as the Attestation Clause, in which the founders witnessed the document. But is that really part of the Constitution?

done in Convention by the Unanimous Consent of the States present the Seventeenth

Day of September in the Year of our Lord one thousand seven hundred and Eighty seven and of the Independance of the United States of America the Twelfth In witness whereof

We have hereunto subscribed our Names

The “Year of our Lord” language is not actually even part of the Constitution itself, which ends at Article VII. The phrase was not debated or ratified by the Constitutional Convention and it seems unlikely that it was even approved by the delegates. In all likelihood, it was a formalism unthinkingly added by the Constitution’s scribe, Jacob Shallus. Perhaps most importantly, the language was not viewed as having any religious significance at the time. In short, the “Year of our Lord” phrase appended to the Constitution has no real legal or historical value.

The fifty words in the attestation clause are not part of the legal document itself. Constitutional scholar and Yale Law professor Akhil Reed Amar explains:

As it turns out—though this fact has until now not been widely understood—the “our Lord” clause is not part of the official legal Constitution. The official Constitution’s text ends just before these extra words of attestation—extra words that in fact were not ratified by various state conventions in 1787-88.

For example, when you sign a contract, that signature is attesting to your consent, it is not part of the terms of the contract. The signatures and dates are not part of the Constitution itself.

Even more importantly, when the printed text of the Constitution was sent to the states for ratification, five of the first nine states that would ratify it only ratified the language preceding the date. In other words, they ratified the text only up to the final sentence in Article VII, and did not even consider the attestations of the witnesses because they didn’t have that language in front of them. “No matter how we count, this closing flourish was never ratified by the nine-state minimum required by Article VII,” concludes Amar in his book America’s Unwritten Constitution. This is crucial; those unratified words cannot be part of the legal Constitution according to the terms of the Constitution itself.

Does “Year of our Lord” appear in any of the drafts of the Constitution?

The first real draft of the Constitution came in early August. George Washington’s copy of this early printed version of Constitution can be viewed, along with all his handwritten annontations, on the National Archives website. It does not contain that “Year of our Lord” verbiage.

The Convention debated and edited this draft for more than a month. They then passed it and the copious edits off to the Committee of Style, a political dream team that included James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and Governeur Morris. The Committee of Style brought the polished product back to the whole convention on September 12, 1787. There is no lordly date on that draft. You can actually see George Washington’s copy of this nearly complete version of the Constitution and his handwritten edits. It runs to four pages and ends with Article VII.

On September 15, the Convention agreed on the complete text, and, for $30, hired Jacob Shallus to engross (transcribe in legible, bold, and occasionally ornate lettering) the final draft onto the four sheets of vellum that reside in that National Archives today.

Shallus worked to complete his work from September 15 through 17. The Convention met on September 17 and read Shallus’s engrossed copy aloud. It was ony then that Franklin made a motion to add on the date and signatures, the motion Madison recorded: “offered the following as a convenient form … ”Done in Convention, by the unanimous consent of the States present the seventeenth of September, &c —”

Franklin’s motion to add the signatures and date was made after this final draft was read aloud, so when it was read aloud it did not include “Year of our Lord.” This also makes sense, Shallus would not have known the actual date of the signing.

In short, none of the drafts contains the “Year of our Lord.” The absence of the date—”Year of our Lord” or otherwise—on the three drafts of the Constitution illustrates the previous point: the date and signatures are not part of the Constitution itself.

Do other years written out in the Constitution contain the Christian reference?

No. The Constitution has several other years written out within the text, and none uses the phrase “Year of our Lord.” Article I, Section 9, and Article V both spell out 1808 as “the Year one thousand eight hundred and eight.”

This is language that the founders debated bitterly—for days in August 1787. That exhaustive debate yielded godless dates. When the framers were responsible for debating, approving, and voting on dating language, that language did not contain the lordly reference.

How did we get “Year of our Lord”?

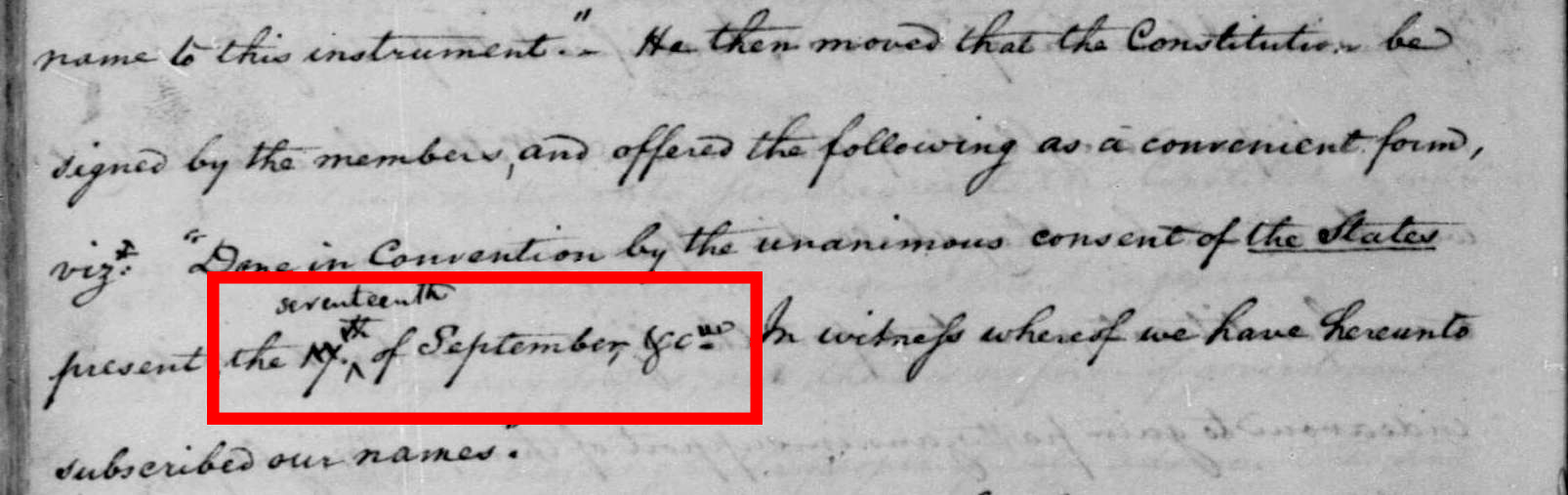

The phrase “Year of our Lord” does not appear in any records of the Constitutional Convention. James Madison recorded the proceedings of September 17, 1787, the day the language was added and the Constitution was actually signed. He notes that Ben Franklin made a motion: “that the Constitution be signed by the members and offered the following as a convenient form viz. ‘Done in Convention, by the unanimous consent of the States present the seventeenth of September, &c — In Witness whereof we have hereunto subscribed our names.'”

Here are Madison’s original, handwritten notes, held in the Library of Congress:

Library of Congress, Manuscript Division.

The actual words “Year of our Lord” are not present in Madison’s notes. Madison’s abbreviation, “&c—” and the appearance of “Year of our Lord” on the final Constitution leaves two possible explanations. First, it is possible that the delegates wanted this dating convention, but that it was so common and unremarkable that Madison didn’t bother to record it. He lumped the “Lord” in with a dry formality, an “etc.” If this is true, and it may be, it seriously undercuts any claim that the founders who adopted our entirely godless document really intended this pro forma language to transform it into a Christian manifesto.

The second possibility is that the founders did not vote on or approve the “Year of our Lord” language, which was instead added later. This second possibility squares with the evidence better than the first.

“Year of our Lord” appears in some other documents, such as the Articles of Confederation and the Northwest Ordinance, but not in the Declaration of Independence. The disastrous Articles of Confederation used the “Year of our Lord” dating custom. On the other hand, the phrase does not appear in the records of the First U.S Congress, except in correspondence from the states, Pennsylvania included, regarding ratification of the Bill of Rights. So it was a convention that might merit an “etc.”, but was not universal. However, it is significant to note that Madison himself was not in the habit of writing “Year of our Lord.” In Gaillard Hunt’s nine volumes of edited Madison papers, the phrase appears exactly once: in a copy of the Constitution.

The most likely explanation seems to be that the engrosser Jacob Shallus added the language of his own volition; the reference was, as Prof. Dreisbach has posited, “merely a scrivener’s touch.” (Dreisbach, Christian Commonwealth, 967) We don’t know much about Jacob Shallus. But what we do know agrees with the hypothesis: Shallus used a familiar, pro forma phrase that had little to no religious significance at the time. First, Shallus himself does not appear to have been religious. According to the only biography about him, The Man Behind the Quill, by Arthur Plotnik, there are no mentions of god in Shallus’s diary of the Revolutionary War or any of his other writings. His sole mention of the ecclesiastical realm, from that diary, paints an unflattering picture. On the march out of Canada, local priests “elegantly entertained” his company: “These priests live like Princes, while their poor Canadians are starving.” Shallus himself was a Freemason, many of whom criticized organized religion.

As an assistant clerk to the Pennsylvania General Assembly in 1787, Shallus worked in the very building where the Convention met, the statehouse (now known as Independence Hall). Shallus may have, however unintentionally, brought a good deal of his own style into the small details of the Constitution. For instance, as the Senate report on this notes, “The capitalization of all nouns by Shallus in the engrossed copy may be dismissed as an innocent matter of style and its reproduction in some editions with the spelling ‘Tranquillity’ in the Preamble is indifferent.” There are variations in punctuation, capitalization and formatting, too. — all minor details unlikely to preoccupy the convention delegates, just like the language preceding the date.

It looks like the Pennsylvania General Assembly, for which Shallus clerked, used this dating convention for more formal and ceremonial moments—to begin each session, for instance. Shallus may simply have slipped into his habit of using “Year of our Lord” on important documents and because the delegates’ attention was directed to more important debates, they didn’t notice the addition, or found it unremarkable, when they were signing immediately after.

What we know of Shallus means that it is unlikely he had any ulterior religious motive for using the lordly verbiage.

At that time, was Shallus’s “Year of our Lord” addition enough to make the godless Constitution godly?

The argument that this dating convention somehow injects religion into our godless constitution is lacking. The argument for the Christian significance of the “Year of our Lord” was not floated until nearly 50 years after the Constitutional Convention. The argument was not made by a jurist or statesman or even a surviving constitutional delegate, but by a reverend sermonizing.

That reverend, Jasper Adams, argued that, by using this language in the date, “the people of the United States profess themselves to be a Christian nation.” Adams was also struck by the mention of Sunday in Article I. The reverend saw the mention of Sunday as a nod to the Sabbath and not, through a dating convention, a recognition of the Sun god for whom the day is named. Similarly, the “Monday” in Article I is never argued to be evidence of moon worship or paganism. Nor has it ever been argued that the Twelfth Amendment honors the god of war, Mars, because it includes the month named after him; or that the Twentieth Amendment honors the two-faced Roman god, Janus for including the month that honors him. These arguments would be risible. But for some reason, using a Christian dating convention is seen by the Religious Right to declare that we are “a Christian nation.”

The greatest point against Adams’ argument is that if the framers really wanted a god in the Constitution, it would have been easy enough. Instead, they chose to exclude gods. Indeed, at the time, the deliberate godlessness of the Constitution was lamented by some pious citizens. That would not have been the case had the “Year of our Lord” language had any genuine devotional significance in contemporary eyes.

“God and Christianity are nowhere to be found in the American Constitution, a reality that infuriated many at the time,” write Isaac Kramnick and Laurence Moore in their seminal book, The Godless Constitution. In fact, “the Constitution was bitterly attacked for its failure to mention God or Christianity.” That’s in part because people at the time didn’t view the phrase “Year of our Lord” as significantly religious.

When the proposed Constitution was announced and the debate over ratification began, people complained about the absence of religion. The ban on religious tests for public office was particularly troubling, but, as one anonymous Virginian complained, the “general disregard of religion” and the Constitution’s “cold indifference towards religion” were issues, too. Charles Turner of Massachusetts warned, “without the presence of Christian piety and morals the best Republican Constitution can never save us from slavery and ruin.” In Connecticut’s ratifying convention, one delegate actually sought to inject god into the preamble.

If the Constitution were already a Christian document because of the “Year of our Lord” addition, all this fuss and opposition would not have happened.

Conclusion

The explanation that agrees with all of the available evidence is one that undercuts any legal, historical, or religious significance the phrase “Year of our Lord” might add to the U.S. Constitution. It certainly cannot prove or evidence any intent to found a “Christian nation,” while the provisions in the document itself and the debate around its deliberate exclusions of religion demonstrate a conclusive intent to adopt a secular constitution.

Authored by Andrew L. Seidel, May 2017