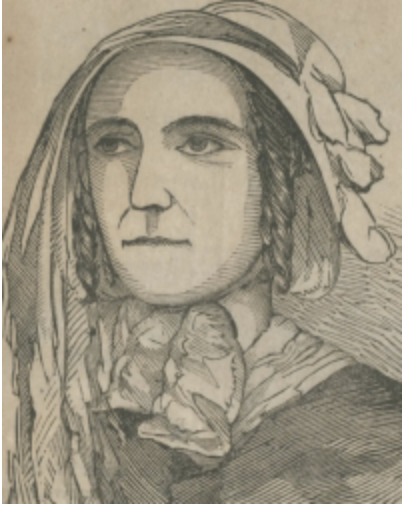

On this date in 1811, Madame Restell (né Ann Trow) — feminist, midwife and abortion provider — was born in Painswick, Gloucestershire, England, the only daughter of Anne (Biddle) and John Trow. She had seven brothers. Their father was an agricultural laborer.

Hers is a rags-to-riches story that ended tragically. She started working as a maid at age 15 and married Henry Summers, a tailor, in 1829. In 1831, after their daughter Caroline was born, they emigrated to New York, where Summers, an alcoholic, died of typhoid a few months later.

She supported herself and Caroline as a seamstress before marrying Charles Lohman, a printer at the New York Herald, in 1833. He was well-educated and frequented a bookstore where philosophers and freethinkers gathered to debate, and he started publishing tracts about birth control.

In partnership with her husband and brother, she started selling patent medicines and herbal contraceptive products advertised under the name Madame Restell. She sold through the mail and made home visits if the abortifacient failed to end a pregnancy. As a self-professed “female physician” and “professor of midwifery,” she built a thriving practice.

“Madame Restell lived in a period where abortion went from being a common misdemeanor in the first few months of pregnancy to literally unspeakable after the Comstock laws in 1873 banned information regarding abortion and birth control,” said biographer Jennifer Wright. “It’s estimated that around 1 in 5 pregnancies during the mid-19-century ended in abortion.” Wright called Comstock “a chronic masturbator.” (Wright interview, Feminist Book Club, Feb. 13, 2023)

Imprisoned for a year at mid-century for performing an abortion, Restell received special treatment from the warden, whose wife prepared her meals. She was allowed to wear her own clothes and have other privileges. After her release, Restell said she would no longer offer surgical abortions but would still provide pills and stays in her boardinghouse, where women with unwanted pregnancies could give birth in anonymity. For an additional fee, she facilitated the adoption of infants. She was granted U.S. citizenship in 1854.

“Lifting passages from the social reformer Robert Dale Owen, she likened abortion and contraception to a lightning rod — an invention that was ‘unnatural,’ perhaps, but sensible and lifesaving. … Pious orphanages did not accept ‘foundlings,’ the product of a live woman’s sin, so many were left in almshouses, where 90 percent would die. A strong cultural belief in hereditary criminality made adoption rare.” (New York Times, Feb. 28, 2023)

She and her husband amassed a considerable amount of money through the years and lived in a capacious Manhattan brownstone at 52nd Street and 5th Avenue. It was built there in 1862, the story goes, to aggravate Catholic Archbishop John Joseph Hughes, who had purchased the adjoining block to rebuild St. Patrick’s Cathedral. The next block over housed the Catholic Orphan Asylum. Hughes denounced Restell from the pulpit for “crimes against God.”

Congress enacted the Comstock laws in 1873. Comstock at times would personally hunt down alleged violators, and in 1878 he surreptitiously bought some pills from Restall, claiming to be a married man whose wife had already given him too many children. He returned the next day with a police officer who arrested her.

There would be no trial, because on April 1, 1878, a maid discovered Restell naked in the bathtub with her throat slit. “A coroner’s jury … viewed the body, and gave a verdict of suicide. The next day the corpse, in a coffin of rosewood, was taken by train to Tarrytown and buried in the plot in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery where Madam Restell’s second husband lay. There was no religious ceremony, and Madam’s surviving daughter was not there.” (The New Yorker, Nov. 15, 1941)

Not everyone was convinced at the time it was suicide. Nor does author Sharon DeBartolo Carmack, who in her 2023 book “Madame Restell: The True Story of New York City’s Most Notorious Abortionist. Her Early Life, Family, and Murder,” presents an argument for “a far more tragic end” to Restell’s life, which ended at age 65. (D. 1878)