By Annie Laurie Gaylor

|

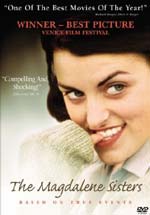

If you missed Peter Mullan’s exceptional film, “The Magdalene Sisters,” during its short airing in U.S. theaters, it’s a must-rent. Even if you caught the foreign release last fall, the movie wears well in a second viewing, and the DVD version contains the bonus of the original BBC documentary, “Sex in a Cold Climate,” that inspired the fictional version.

Set in 1964 Dublin, the movie focuses on several wards of the notorious Magdalene Sisters Asylum, the laundry institutes of punishment run for the profit of the Roman Catholic Church. An estimated 30,000 Irish women were condemned to servitude in them in the 20th century. For some of them it was a life sentence.

The institutes originally targeted prostitutes. Then the definition of “fallen women” was expanded to encompass any young woman who had sex outside marriage, or even came “under suspicion.” Sex outside marriage was considered by the Roman Catholic Church, like murder, to be a mortal sin.

By the 1940s, a majority of the inmates of the ten Magdalene asylums were unwed mothers, working relentless hours of penance cleaning dirty linen from early morning ’til late at night, six days a week. Work, prayer, silence and atonement were preached.

The film opens by showing how three young women find themselves suddenly enslaved at a Magdalene institute. Upright young Margaret, played by Anne-Marie Duff, is raped by a cousin at a wedding. Breaking a taboo by telling on him, Margaret is hustled off the following morning by the local priest to join the Magdalene Sisters.

Bernadette, a flirty orphan with wide green eyes and glossy black hair, is whisked away simply for attracting too much male attention on the playground. Actress Nora-Jane Noone makes her defiant, occasionally cruel character sympathetic. Rebelling at her unfair fate, she exclaims: “All the mortal sins in the world wouldn’t justify this place!”

Warm-hearted Rose, played by Dorothy Duffy, has just given birth and wants only to hold her baby. Her mother won’t speak to her in the hospital, and she is coerced into signing away her child, told by her priest that her “bastard child [would otherwise be] rejected and scorned by all decent members of society.” The same shell-shocked day she finds herself locked in the grim, barred dormitory behind the unpassable gates of a Magdalene institute, suffering excruciatingly as her milk builds up.

We also meet a young, unwed mother already there–a gauche, trusting girl who has been renamed “Crispina” in a cruel joke by the mother superior. Sister Bridget tells the lank-haired young woman, embodied by Eileen Walsh, that the name means someone with curls.

Sister Bridget is deftly played by actress Geraldine McEwan as a sinisterly soft-spoken sadist. She smiles at her tormentees before inflicting punishment. Busy counting all the cash, Bridget scarcely looks up as she orients the three new inmates. Working in the laundry will cleanse their souls, she tells them.

Scenes will haunt you. In one Oliver Twist-like scene, nuns gorge on a cornucopia of savory dishes as their charges eat gruel. Shaving heads, with lots of gratuitous cutting of scalps and blackening eyes, was a common punishment. After Bernadette’s hair is hacked off, the camera shows an extreme close-up of her eye, the lashes coated in blood. Reflected in her pupil is the image of Sister Bridget forcing her to look at herself in a mirror to see “how she really looks.”

The most unforgettable scene takes place in the lavatory, where a group of naked inmates is humiliated by two unattractive nuns picking out the “biggest bum,” the smallest breasts, and worse.

As a Christmas carol with the refrain “O tidings of comfort and joy” plays, the camera pans the joyless, comfortless dormitory with its huge posters reading: “God is Just,” “God is Good.”

Margaret, discovering that Crispina is sexually serving the priest, plans a petty revenge on the priest that unwittingly sets up her friend for an even worse fate. No one who sees this film will ever forget Eileen Walsh screaming out: “You’re not a man of God!”

At the film’s conclusion, a chilling blurb announces that the last Magdalene institute closed only in 1996.

As a former ward recalled in the documentary, “The Sisters of Mercy showed us no mercy.”

“The Magdalene Sisters” ends on an optimistic note, with the three main protagonists being “sprung.” Perhaps this sugarcoated the reality, but it makes the movie easier to watch. While it all sounds very grim, “The Magdalene Sisters” transcends through art. The script, editing and acting are tight as a poem. It deserved its “Best Picture of 2002” vote by the Venice Film Festival. But I suspect Peter Mullan, the Scottish actor who directed and wrote this movie, was even more pleased by the sharp criticism from the Vatican.

Annie Laurie Gaylor is editor of Freethought Today.