On this date in 1952, William Tass “Bill T.” Jones was born in Bunnell, Fla., the 10th of 12 children born to Estella (Edwards) and Augustus Jones, migrant farm workers. The family followed the crops north and settled when he was 3 in Wayland, N.Y. “I am a child of potato pickers who wept at the Civil Rights Act of 1964, because they knew what it meant,” Jones later said. “They knew what had been denied them before.” (The Guardian, June 11, 2004)

He starred in track in high school and participated in drama and debate. After graduation he enrolled at the State University of New York at Binghamton, where he studied classical ballet and modern dance and took classes in west African and African-Caribbean dancing. Binghamton was where he fell in love with Arnie Zane. Their personal and professional relationship lasted until Zane’s death from AIDS in 1988.

With Lois Welk and Jill Becker, they formed American Dance Asylum in 1974 and began emphasizing a partnering technique called contact improvisation. Jones created a number of solo pieces during this period and performed in New York City. Interested in living in an area more supportive of the arts and of an interracial gay couple, he and Zane moved in 1979 to Rockland County just outside the Bronx.

Their duets featured photography, singing, and spoken dialogue with a political and social focus and acknowledgement of their personal relationship. A trilogy they created in 1979-81 — “Blauvelt Mountain,” “Monkey Run Road” and “Valley Cottage” — broke choreographic ground.

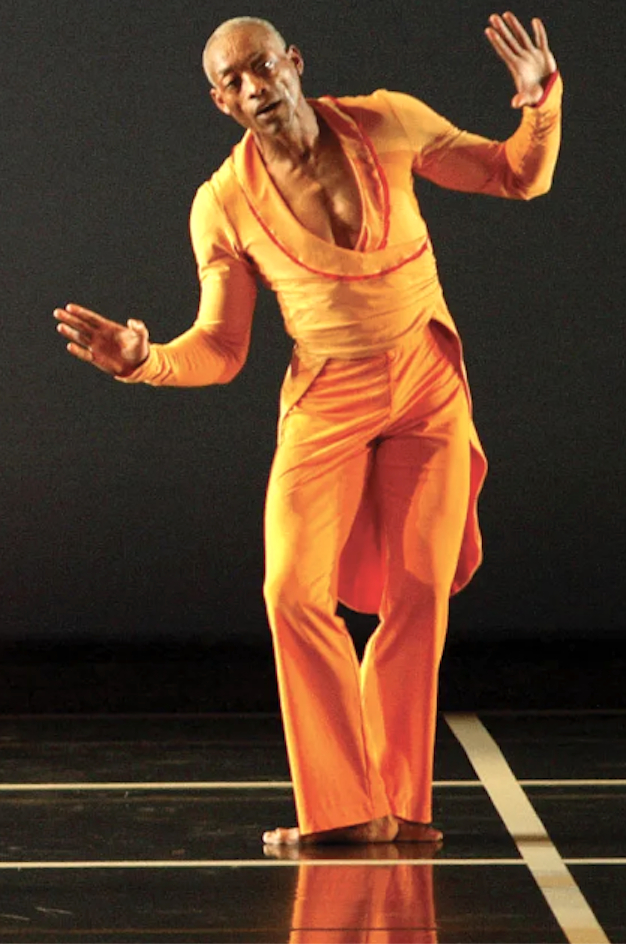

They formed the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company in 1982, recruiting nontraditional performers representing different body sizes, shapes and colors. “Jones, a choreographic provocateur, presents his ideas about identity, art, race, sexuality, nudity, power, censorship, homophobia and AIDS-as-chemical-warfare with a streetwise, in-your-face attitude,” said a 1998 entry in the “International Encyclopedia of Dance.”

“Last Supper at Uncle Tom’s Cabin/The Promised Land” (1990) explored differences not only in body shapes but attitudes, race and sexuality. It was also about Jones’ conflict with faith, despite growing up in a devoutly Christian home. He has called it “a dialogue with my mother’s faith.” (Which never included 52 nude bodies dancing à la the piece’s fifth and final section.) “Last Supper” questioned how God could allow the cruelties of slavery and AIDS to happen. Zane had died in 1988 at age 39 of AIDS-related lymphoma. Jones’ piece “Absence” evoked his memory.

In an interview with Jeffrey Brown (Oct. 8, 2021) for “News Hour” on PBS, he told Brown “I’m an atheist.”

“Still/Here” (1995), a major midcareer work, was controversial in some quarters. It was “a meditation about mortality in which Jones incorporated the movements of terminally ill people whom he’d met in the free dance workshops he’d set up for them, the patients becoming, in a sense, collaborators.” (New York Times, June 6, 2016) New Yorker dance critic Arlene Croce called it “victim art” and refused to see the production.

With over 120 works for his own company, Jones has also choreographed for Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater and numerous other companies. “Arguably the most written-about figure in the dance world of the last quarter century, Jones is inarguably the most broadly laureled, with a National Medal of Arts and a Kennedy Center Honor and Tony Awards and a Dorothy & Lillian Gish Prize and a MacArthur Fellowship and, without hyperbole, scores more.” (Ibid.) His memoir “Last Night on Earth” was published in 1995.

Jones is married to designer and creative director Bjorn Amelan, a French national raised in Haifa, Israel, and several European countries. They have been together since 1993, when he started designing many of Jones’ sets.