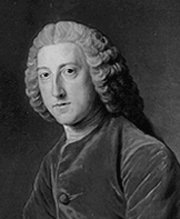

On this date in 1708, William Pitt, statesman and the first Earl of Chatham, was born in England. Educated at Eton and Oxford, he entered Parliament at age 27 in 1735. After one of his speeches in 1736 offended the king, Pitt was dismissed from the army. He continued eloquent calls for reform in the House of Commons, served in several prestigious posts and in 1756 was named leader of the House. Pitt, known as “the Great Commoner,” was England’s most powerful politician by 1760 and was known for his honesty. (He’s also referred to as Pitt the Elder to distinguish him from his son, William Pitt the Younger, who also was a prime minister.)

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, was named for Pitt, who served as prime minister during the Seven Years’ War against the French in the colonies. He argued in Parliament against the Stamp Act and introduced many measures to placate the Americans, which were all voted down, such as recalling British troops from Boston. Pitt advised, “You cannot conquer the Americans.” The king consequently called him “a trumpet of sedition.”

Pitt was believed by some to be author of an unsigned “Letter on Superstition” published in the London Journal in 1733 and reprinted with his name in 1873. It called for a “religion of reason.” Biographer Basil Williams in his Life of William Pitt (1913) disputed that claim. Yet Williams’ research found that Pitt was a deist with “a simple faith in God,” who wrote a “fierce denunciation” of those with a “superstitious fear of God.”

There is agreement Pitt had no ministration from the church on his deathbed. “Lord C[hatham] died, I fear, without the smallest thought of God,” recalled William Wilberforce, a friend of Pitt’s son (Correspondence of William Wilberforce, 1840). Pitt, who suffered from gout most of his life, collapsed at age 70 during debate on granting independence to the colonies, which he opposed, and died shortly thereafter. (D. 1778)