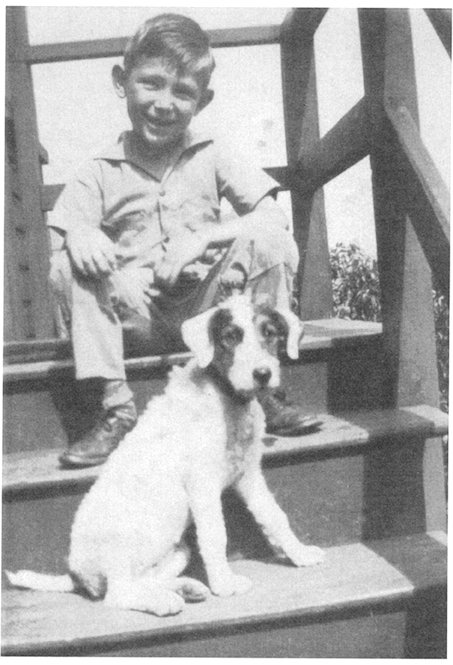

You can ask anyone — my childhood friends, my relatives — I was a good boy. I did as I was told, took school seriously, was polite and well-behaved, showed respect to my parents, other adults and persons of authority.

You can ask anyone — my childhood friends, my relatives — I was a good boy. I did as I was told, took school seriously, was polite and well-behaved, showed respect to my parents, other adults and persons of authority.

And, of course, I went to Sunday school and church every week and said my prayers nightly.

I wasn’t perfect. The entry for April 1, 1940, in the only diary I’ve ever kept, reads, “Tonight mother and I well, you might say fighting.” But I was capable of remorse (Jan. 28): “Grandma Kint is awful sick, and doesn’t know anybody. I’m awful sorry.” I was also sorry on Jan. 11, when I “got Mother mad.” Doesn’t it take a good boy to show remorse, even to himself?

Rereading this 70-year-old “text,” I notice that although my diary often refers to the movies I saw almost every Saturday, it never mentions the church I attended every Sunday, the First Presbyterian Church of McKeesport, Pa. That’s surprising, because for my family, attending church was a big deal.

One Sunday, the minister confidently told us that our loved ones who had “passed away” were forever looking down from heaven and watching not only what we did, but even tuning in to what we thought. Oh oh! That meant that my late Great-grandma Kint and Great-aunt Laura were privy to their good boy’s occasional naughtiness and “wicked” thoughts.

It didn’t occur to me that our pastor may have been wrong about the heavenly monitoring stuff, although I wasn’t much given to theological speculation.

My parents, like most good Christians of the era, were not aggressively bigoted. I can’t recall them saying much that was really vicious against Jews and Catholics. (We knew no “Negroes” except for “Amos and Andy” and Jack Benny’s faithful Rochester.) But over time, I received from my parents and extended family the almost subliminal message that Jews and Catholics were different from us and not as good as us. (In their minds, Negroes were obviously inferior.)

This posed a problem. A Jewish family bought the little grocery just up the street, and their son, Irving, was my age. It was great to have a new friend. We had good times playing together. He really didn’t seem any different from me. And his parents were “nice,” the highest form of approbation in our circle. So what was this “Jew-ness” then? The parents of my Catholic friends also were “nice,” too, and in western Pennsylvania, very much in the majority. Catholic kids also went to church on Sunday and said their prayers.

One thing set my Protestant family apart and led to my first excursion into theology. My Catholic friends could go to Sunday afternoon movies, and I couldn’t. Turned down once again after begging, I said, “But Dad, you go to baseball games on Sunday!” His answer set me firmly on the road to freethought: “Well, if Jesus were alive today, he would go to ballgames on Sunday, but not to the movies.” The exquisite lameness of that rejoinder hung in the air between us.

In the innocent ’40s, what seemed to be most sinful, most likely to turn a good boy bad, was, of course, S-E-X. Sex was simply not discussed at church, at home or at school, but was somehow in the air in all these places, and it worried good boys like me. But hormones will be hormones, and I actually found my first “true love” in church. Jean’s piety, alas, had nothing to do with it.

Off to college

When I turned 17, my parents said that I could either go to the University of Pittsburgh and live at home or attend a “small Christian college” 25 miles away and live on campus. Duh! At Washington & Jefferson College, which was only nominally Christian, the good boy discovered philosophy, a required two semesters in sophomore year, taught by a refugee German professor who I now realize was a thoroughgoing secularist.

When I turned 17, my parents said that I could either go to the University of Pittsburgh and live at home or attend a “small Christian college” 25 miles away and live on campus. Duh! At Washington & Jefferson College, which was only nominally Christian, the good boy discovered philosophy, a required two semesters in sophomore year, taught by a refugee German professor who I now realize was a thoroughgoing secularist.

Then there were two semesters of logic from a World War II conscientious objector, a rara avis in my God-and-country background. He would become a lifelong friend. Naturally, the good boy said nothing about these alarming persons to his parents.

The Christian life was something my family circle all understood, though practiced indifferently. The life of the mind, however, was terra incognita to them and to me, and as I gradually discovered it the experience became life-changing. I added a philosophy major to my existing English major. I did well enough to be invited to join the philosophy honor society.

Although I was not then familiar with the term, my freethinking was quietly roiling my familial life. Once or twice a month I would hitchhike home to go on Saturday night dates, borrowing my dad’s car. The problem was that on Sunday morning I was expected to accompany them to church. To avoid a confrontation I dreaded, I did just that. In short, I faked it, just going through the holy motions.

In my imagination, I wore on my sport coat an “H” for hypocrite. It became extremely difficult to enter the gates of the Brookline Boulevard United Presbyterian Church with thanksgiving. My father was an elder and church treasurer there. As I sat in the pew, I would have out-of-body experiences in which I saw the good boy in the similitude of piety and found him contemptible.

A few months away from college graduation in 1952, my hypocrisy had become almost unmanageable. Something had to give. So like a good freethinker, I sat myself down and thought how I might best break to my parents the news that I would no longer attend church with them.

I knew that initially they’d be shocked and upset, but also fairly sure that the boy philosopher would be able to explain his thinking to them, maybe even reconcile them to his freethought. “After all,” I mused, “we’re adults. We can sit down and discuss this rationally.”

Moreover, I was still a good boy, about to graduate magna cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa, with honors in English and philosophy, with an acceptance to Harvard Law School. Surely all that should moderate the shock, perhaps mitigate their inevitable displeasure.

Wrong! There was to be no careful explanation, no extended discussion. (Indeed, there was never to be any further discussion of religion for the more than 40 years my parents would be with me.) All I managed to get out was that I would no longer in good conscience attend church because I no longer believed in the Christian religion.

My father looked thunderstruck. My mother started to cry. They left the room. The next day, my father came to me and said, “Your mother and I have decided that since education has turned you from God and the church, we’re not going to support your education any further.”

I had been a bad boy — no Harvard for me. So much for Christian charity.

I soon decided to enlist in the Army for three years and to use the G.I. Bill to help put myself through law school. A year later, on a troop ship in the mid-Atlantic, I decided to pursue a Ph.D. instead and become an English teacher. My parents, being really good and kind people at heart, eventually became reconciled to their heretic son and were usually there for him as he was building a family and a career.

But even in their old age, as they became somewhat less intense about their Christianity, I couldn’t be sure that they were ever able to think of their only child as a good boy again.

After 36 years of teaching and writing, FFRF member Dr. Roger Rollin, professor of literature emeritus at Clemson University, now enjoys raising a ruckus in the Carolina bible belt. He titled his Easter Sunday talk to the Tryon, [N.C.] Unitarian Universalists “That’s Blasphemy, God Damn It!”

Rollin notes: “For public consumption, the UU’s changed the title to ‘That’s Blasphemy, for Goodness Sake!’ (which sends a strangely mixed message).”