James A. Haught, Editor in Chief

Charleston (W.V.) Gazette |

By James A. Haught

Nobody actually knows where beliefs come from. Psychologists can’t explain what makes some people religious skeptics and others believers–or why some become conformists and others become rebels, or political conservatives and liberals, or war “hawks” and peace “doves,” or puritans and playboys, or death penalty advocates and opponents, etc.

Therefore, I don’t know what caused me to be a doubter while my classmates were believers, some even becoming preachers. All I know is my own story:

I was born in 1932 in a little West Virginia farm town that had no electricity or paved streets. My family had gaslights, but farmers outside town lived with kerosene lamps, woodstoves, and outdoor toilets.

I was sent to Bible Belt Sunday Schools, and tried to pray as a child. But an awakening occurred in my teen years. In high school chemistry class, I learned how gaps and surpluses in outer electron shells cause atoms to bind into molecules, making almost everything in our world. It was a revelation explaining much of existence. Science became an obsession, a portal to understanding reality. Slowly, religion’s claims of invisible gods, devils, heavens, hells, angels, demons, miracles and messiahs turned into fairy tales.

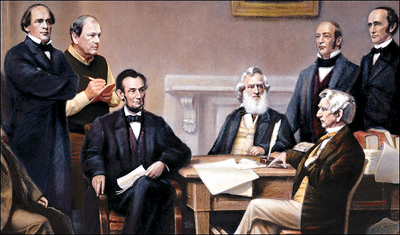

“I’ll be 76 soon. For a previous birthday, the Gazette staff cooked up this comment on my longevity in the news biz.”

|

Rather by accident, I lucked into a newspaper job, and my world expanded. A cynical city editor laughed at “holy rollers” and huckster evangelists. We debated religion. I agreed that supernatural church claims are baloney–but I had a quandary: If the magical explanations are nonsense, I asked, what better answers exist? Why is the universe here? Why do we live and die? Is there any purpose to it all? Is everything random? What can an honest person say? What answer can a person of integrity give?

He eyed me sharply and replied: “You can say: I don’t know.” Bingo! Immediately, a path of honesty opened for me. Previously, I had sensed that it’s dishonest for theologians to claim supernatural knowledge without any proof, but I had lacked a truthful alternative. Now I had one. I could quit agonizing and admit that ultimate mysteries are unknowable.

I joined a skeptical Unitarian group, read physics and philosophy books, and cemented a scientific worldview. Beliefs should rest on intelligent evidence, not on fables. Eventually, I saw seven logical reasons why thinking people should reject church dogmas:

- Horrible occurrences such as the Indian Ocean tsunami that drowned 100,000 children prove clearly that the universe isn’t administered by an all-loving invisible father. No compassionate creator would devise killer earthquakes and hurricanes–or breast cancer for women and leukemia for children–or hawks to rip rabbits apart and pythons to crush pigs and sharks to slaughter seals. A creator who concocted such things would be crueler than people are. In philosophy, this dilemma is called the Problem of Evil. It doesn’t disprove the existence of a heartless god, but it wipes out the merciful god of churches.

- Hundreds of past gods and religions have vanished, and are laughable today. Zeus’ Pantheon atop Mount Olympus was so real to ancient Greeks that they sacrificed thousands of animals to the imaginary gods and goddesses. Are today’s deities any more substantial?

- Although churches claim that religion makes believers loving and brotherly, the historic record shows opposite results. Human sacrifice, holy wars, Inquisition torture chambers, massacres of heretics, Crusades against infidels, witch hunts, Reformation wars, pogroms against Jews, Jonestown, Waco, nerve gas in Tokyo’s subway, suicide bombings by today’s Muslim fanatics–all these undercut the kindly image of believers.

- Most of the brightest thinkers throughout history–philosophers, scientists, writers, democracy reformers, and other “greats”–have been skeptics. Omar Khayyam, Michel de Montaigne, William Shakespeare, Voltaire, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Paine, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Charles Darwin, Leo Tolstoy, Mark Twain, Thomas Edison, Luther Burbank, Sigmund Freud, Bertrand Russell, Albert Einstein, Margaret Sanger, Will Durant, Jean-Paul Sartre, Isaac Asimov, Kurt Vonnegut, Carl Sagan–this is illustrious company. If the best minds couldn’t swallow supernatural tenets, why should we?

- Scientific thinking requires detectable, testable evidence. But religion offers no proof except writings left by long-dead holy men. Muhammad said the angel Gabriel dictated the Koran to him. That’s proof enough for a billion Muslims. Joseph Smith, a convicted fraud artist, said an angel named Moroni helped him find buried golden tablets, which he translated into miracle-filled scriptures. That’s proof enough for millions of Mormons. But honest seekers need something more tangible.

- Despite the common assumption that church leaders are more moral than ordinary folks, a horrifying number of ministers and priests are child-molesters, swindlers, adulterers, or half-cracked charlatans. A few even commit murder. (Freethought Today logs their astonishing rap sheets in the “Black Collar Crime” section.) There’s no evidence that religion makes them holier than thou.

- All church predictions of miraculous events have been flops. Millerites waited on hilltops for a Second Coming that didn’t come. Jehovah’s Witnesses set several wrong dates for Doomsday. Fundamentalists thought the 2000 millennium passage would bring heavenly havoc. The Rapture probably will be another rupture.

Over the years, I’ve spelled out these premises in seven books and 60 magazine essays. (A book list accompanies this personal account.) I even hatched a freethought novel focused on religious absurdities in ancient Greece.

To me, the bottom line is honesty. A person with integrity doesn’t claim to know supernatural things that he or she doesn’t know. An honest person wants solid evidence to support assertions, and is leery of baseless claims. Therefore, skeptics are the most honest of all.

James A. Haught freethought book list:

Holy Horrors (Prometheus, 1990). Translated into Spanish as Horror Sagrado, Turkish as Kutsal Dehpet, Portuguese as Persguicoes Religiosas, and Polish as Swiety Koszmar.

Illustrated Answers to 100 Basic Science Questions (Prometheus, 1990). Translated into Polish as Nauka w Nanosekunde and Italian as Il Vuoto di Torricelli.

Holy Hatred: Religious Conflicts of the ’90s (Prometheus, 1995). Translated into Japanese by Jiji Press, and into Turkish as Kutsal Nephret.

2,000 Years of Disbelief: Famous People With the Courage to Doubt (Prometheus, 1996).

Holy Horrors (expanded paperback after 9/11) (Prometheus, 2002).

Honest Doubt: Essays on Atheism in a Believing Society (Prometheus, 2007).

Amazon Moon, a freethought novel of fabled women warriors, focusing on religious sacrifices, oracles and Sacred Wars in ancient Greece (BookLocker, 2007).