Mobile Menu

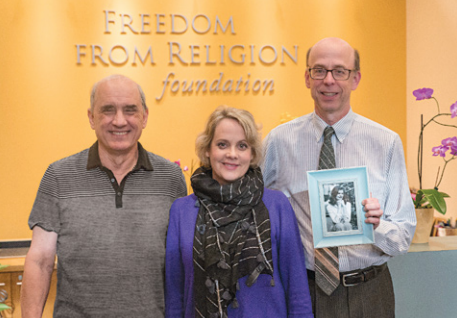

Lauryn Seering

2017 Michael Hakeem Memorial College Essay Contest Fourth Place (tie) By Gabrielle Goldworm

Empathy, not God, is basis for morality

FFRF awarded Gabrielle $750 for her essay.

By Gabrielle Goldworm

It is not an exaggeration to say that my father and I were likely the only "true" atheists in my town. I grew up in a red state — one of the reddest, in fact. Idaho was one of only four states that would have still gone red had Millennials voted en masse, and like most deeply red states, life there comes with a healthy dose of guns, gumption and God.

There were two big groups in my tiny town of Sandpoint: the Mormons and the Mennonites, though the Jehovah's Witnesses could give them a run for their money.

Then there was the odd Lutheran, Baptist, Catholic, or pseudo-spiritual hippy dippy church that housed all the noncommittal folks scattered across the landscape. In Sandpoint, even if you weren't religious, you were spiritual.

My parents moved to this picturesque town from the East Coast, bringing with them a cynicism that made them stick out like sore thumbs and that made me come off as just a bit odd to my spiritual, western classmates. I was born there; I grew up in the pretty incubator that was Sandpoint, Idaho, but growing up different admittedly made it hard.

Growing up atheist made it even harder.

I can remember in shining detail what it felt like at age 6 to tell my classmates that I didn't believe in God, and have them look horrified or confused. I can remember what it was like to have missionaries show up on my doorstep every other weekend and ask me if I was sure I didn't want to just change my whole perception of reality.

I remember sitting in class in third grade, refusing to apologize to a girl who claimed that a joke I had made had been attacking "her God," and having my parents called because of it. I can remember my first boyfriend, a Mormon, dating me because I was a form of rebellion, and knowing that his parents hated me, even though they would never say it.

Kids hate feeling left out, and nothing makes for a less attractive friend then someone who doesn't even perceive the universe in the same manner as you.

One would think that all this would have worn me down. Actually, it was quite the opposite. I firmly believe that growing up in that environment reinforced my conviction that you don't need God to have morals, and you certainly don't need to be a nonbeliever to lack them.

The Mennonite men in my town walked around in modern clothing, smoking, drinking and swearing all they liked, while their wives and daughters trailed behind them, dressing and speaking like something out of "Little House on the Prairie." Many of the Mormons in my high school were hardcore potheads, who smoked and snuck out to eat coffee ice cream at the beach as their own form of teenage rebellion. Many of the Mormon men in my town had converted in order to marry hot women who wouldn't sleep with them otherwise.

Many of the most staunch believers were former abusers, drug addicts or basic misanthropes who found themselves at rock bottom and climbed onto the pedestal of organized religion so that they could look down on the nonbelievers, those still "fumbling in darkness," and shake their heads.

I never did drugs in high school. I never stole, never bullied and never treated someone differently because of what they believed. I cannot say the same for most of my God-fearing peers. My morals come from empathy and a deep desire to see the human race succeed and better itself, influenced by my family and close friends.

I do not "hate" the concept of God; I consider myself ambivalent. But I didn't need God to be a good kid, and I don't need him to be a good adult.

Gabrielle, 19, is from Sandpoint, Idaho, and attends Seton Hall University, majoring in international relations. She enjoys writing and reading fiction and nonfiction, especially regarding atheism. After graduation, she hopes to work in the field of national security and travel around the world. She is a member of the Secular Student Alliance.

2017 Michael Hakeem Memorial College Essay Contest Fifth Place By Violet Richardson

Caring, compassion are the moral standards

FFRF awarded Violet $500 for her essay.

By Violet Richardson

I grew up in a household that could accurately be described as "godless." I was not educated by religious scholarship or kept in line with reminders of divine consequences. I was not set on a path of righteousness paved with bible stories nor was my sense of justice instilled on the basis of any god's will. As such, I do not believe that the moral code that I follow can be credited to God.

Instead, my understanding of right and wrong has been formed via the choice to practice empathy and compassion in my everyday life. When considering my own behavior, I imagine how it will affect the people around me rather than how it will be judged by God. I imagine the feelings of others based on how I would feel in their shoes. I do not need a cosmic middleman to tell me that I possess no right to make other people suffer.

Despite what I consider to be an inherent human trait, many people of faith do not believe that those outside of their religion, or any other religious following, have the ability to lead just and moral lives. Godlessness is associated with violence and chaos, which leads atheists and agnostics to be stereotyped as dangerous undesirables. Given humanity's long history of war and aggression committed by those among the ranks of believers, and frequently in the name of God, this assessment appears patently unfair.

Conflating piousness with morality is far more dangerous than the choice to live a life without religion. To do so allows for the justification of wrongdoing by those who claim to act in line with the word of their god. To do so opens the door for preemptive persecution of anyone deemed a nonbeliever, whether that is how they identify themselves or not.

Personally, I do not consider myself a believer. I do not discount the possibility that a higher power may exist, but if so, that truth has failed to reveal itself to me. Though I sometimes long for the comfort of believing that everything happens for a reason, that I am watched over by a kind, all-knowing being, and that I am destined for an eternity of happiness in the afterlife, I have yet to be convinced.

Regardless of whether we possess immortal souls, each of us is given the opportunity to make the best of our finite time as the people that we are. Instead of viewing this reality through a negative and nihilistic lens, I and many others take this to mean that we are all responsible for making our time and the time of those we live with as positive as possible. In recognizing that our own life is finite, we can recognize that the same is true for every other living creature and that they all deserve to experience the same happiness and security that we want in our own lives.

If we are to live but once, we should do so in a loving and generous way. Choosing a life of positivity, of caring for your community as you care for yourself, is the best way to not only dispel the negative stereotypes surrounding "godlessness," but it is also the best way to set an example for anyone who wants to live their lives in a moral way. My morals do not come from God, they come from understanding this fact.

Violet, 22, is from Madison, Wis., and attends the University of Wisconsin, majoring in international studies and political science. She is currently spending a semester abroad in France. She hopes to attend law school to become a lawyer to help people who are vulnerable and disadvantaged.

Morality exists within ourselves, not religion

FFRF awarded Kaylee $400 for this essay.

By Kaylee Payne

One would think it would be easy enough to discount the notion that a person who is religious is inherently more moral than anyone else. After all, there are many cases, both historically and in the modern day, of religious individuals who are dishonest or cruel.

Yet bringing up this point generally earns a rebuttal along the lines of "They're not actually representative of the religion if they do those things," helping to keep the "No True Scotsman" fallacy alive and well and endlessly frustrating nonbelievers. What, then, is a person to do when faced with the myth that morality solely belongs to, and is a direct result of, religion?

Part of the difficulty of dispelling this idea is how firmly ingrained it is in the public consciousness.

Revealing that I am an atheist has been at times met with revulsion. Other times, well-meaning but tactless individuals can't help but express shock that someone "as nice as I am" fails to harbor belief in any sort of deity. It doesn't seem to occur to such people that perhaps my lack of faith has nothing to do with my personal moral compass, but is simply my acknowledgment that there is little to no evidence of the existence of mystical deities. The skeptical side of me refuses to believe anything without sufficient proof.

Nor do I believe that thousand-year-old texts written in the context of different times are a reliable source for my morals. Never mind that behaving in a moral manner only because of commands in an ancient book is a rather dubious attitude. Rather, I don't feel I need any excuse to treat my fellow human

beings well beyond the fact that I am one of them, and am capable of feeling an emotion that presumably has been present since the days of our earliest ancestors: empathy.

Every person who has ever lived has been hurt. They have experienced misery and suffering and the unfairness of the world. I am no exception. Some in such a position become bitter and hard, and close their hearts off to all. Some, though, use their pain as inspiration to become better people, to work to create a world where no one else has to suffer as they did. I hope to fall in the latter category.

We are all the heroes of our own stories, but also the supporting characters of someone else's, and when the people I have known reflect back on the sagas that are their lives, I wish that they will find no reason to see me as their story's villain, who worked at every turn to harm them. No deity told me to be concerned with the welfare of others; I do so completely of my own free will.

However, as time has passed, I've found that fewer and fewer people who know me express dismay at my lack of faith upon learning of it, despite living in a rural area where my beliefs are at odds with most people's. Perhaps it is just a matter of learning to look past such trivial differences as religious beliefs in order to see what really matters: how we treat others.

I've seen both theists and atheists alike concerned with nothing but deriding all members of the other party as stupid and immoral, and such behavior benefits no one. Whether morals are from within or are claimed to be derived from a god, the important thing is that they are based on goodwill, something the world could always use a little more of.

Kaylee, 19, is from Fort Blackmore, Va., and attends University of Virginia's College at Wise. She is working toward earning certification in teaching English as a second language (ESL). She plans to spend her junior year in Chile and then work in the Peace Corps after graduation.

FFRF College Student Essays honorable mentions

FFRF awarded $200 to each of the honorable mention winners. Their essays are excerpted here.

Reason can solve moral problems

By Christopher Bednarcik

Asserting that one's morals should come from God requires a person to first believe that God exists, and if so, believe that God actually cares whether we're moral or not.

Most followers of religion, especially in the United States, believe that God does exist and that he communicates his rules for appropriate living through the bible. However, upon personal examination, I've determined that the bible is not an acceptable moral compass.

I think the best source of morality is human reasoning, structured around skepticism and a scientific approach to solving complex ethical issues.

We should focus on outcomes of our behavior — the consequences. Rather than seek solutions through a revealed religion, we should ask ourselves whether our actions are just and fair. Who, if anyone, will be harmed by my actions?

When I encounter a tough decision, I take a cost-benefit approach. I ask myself if my actions would violate any of my personal virtues, and if not, I apply a variety of other frameworks, such as utilitarianism or individual rights. By taking a broad approach, I try not to harm others.

I'm an atheist because following a revealed religion based on the existence of a deity that I cannot prove exists doesn't make sense to me. I'm an atheist because religious texts don't hold up to reasoning and science. Mathematics describes the world the way it is. We don't need the god of an ancient text to guide us.

Christopher, 19, is from Lockport, Ill., and attends North Central College. He is majoring in mathematics and plans to be a high school math teacher. He is an Illinois State Scholar and a member of the National Society of Leadership and Success.

The truth about morals set me free

By Michael Brown

I was told that all were equal in God's eyes, but I was despised for my mixed heritage. I was told that God's plan shouldn't be altered with medicine or vaccinations, yet when the pastor needed a triple bypass, it was found to be within both God's will and the church's pocketbook.

By the time I was removed from my home, placed in the foster care system and ultimately emancipated, I had realized that morals are inherently human creations. I stripped away my religious upbringing and sought to form my own code of conduct, without the threat of eternal damnation.

When we attach morals to godliness, the interests of a single perspective take on a divine, generational immortality and proliferate absolutist ways of thinking as a dominant social force. This allows antiquated ideas to stunt social development for centuries, leading to oppression of minority populations.

It became clear to me that religious codes are genuinely inadequate to direct society because their perversion of morality convolutes the "moral" course of action, and fundamentally deals in absolutes that do not allow for diversity of thought.

I discovered agency, embraced empathy, and leveraged my experiences with racism, homelessness, and trauma to create a moral code that put humanism and compassion above any ethereal, imagined restrictions on who deserves to be treated as a human being.

Michael, 21, is from Hanover, N.H., and attends Dartmouth College. He had a tumultuous time growing up in the foster care system, but overcame those struggles and is now seeking a degree in biology. Eventually, Michael would like to earn a degree in osteopathic medicine.

Choose the Right

By Catherine Evans

Choose the Right. CTR.

Those three letters held a significance to me growing up, whether I was singing about them in Mormon children's songs or wearing them around my finger on a child-sized green ring. A daily reminder that God was always watching, blessing me when I was obedient and taking notice when I chose the wrong.

Choose the Right was confirmation that my lifestyle was dictated by the words of God, while everyone else was choosing the wrong. My decisions had already been made for me, and I just needed to follow the plan.

Over time, though, CTR started to lose some of its weight. I started to question what it was that made an action "right" and what made my non-Mormon friends' actions "wrong." I started to realize that my friends based their decision-making on similar grounds, yet they ultimately came to different conclusions.

For example, I was taught that homosexuality was wrong, and it was not until I met people who identified as queer that I began to recognize the moral ambiguity of this belief. My "Choose the Right" moral compass is always present, but it evolves when I meet people who cause me to question my ideas of right and wrong.

Morals come from within, shaped by experiences and interactions. They evolve through feelings of empathy and guilt, imbued by the society of which we are a part. They guide decision-making, though our ideas of right and wrong vary dramatically.

Though its meaning has changed, and will never stop changing, the phrase "Choose the Right" still reflects how I strive to live my life.

Catherine, 20, is from Herndon, Va., and attends James Madison University. She is involved with the university's College Democrats organization. She is majoring in rhetoric and technical communications and will graduate a year early from the Honors College at JMU.

Helping as a matter of course

By Nicholas Giurleo

One day, two female missionaries had approached me, trying to hand me a pamphlet. I noticed one of the women, as the other was talking, had very noticeably and suddenly become pale. She took a step back and seemed extremely disoriented. As I asked her if she was OK, she collapsed onto her knees.

Her companion immediately panicked and backed away in fright. I knelt down and lifted the woman's head up. She didn't lose consciousness, but she seemed very weak. I reached into my bag and offered her water and a granola bar. I stayed with her until two police officers arrived.

"Thank you. It is so comforting to know that there are good Christians like you in the world who go out of their way to help their brothers and sisters in need," she said.

I smiled and said, "You're welcome, ma'am, but I have to say, I'm no Christian. I'm just a guy with a conscience. Hard to believe an atheist could do something good for a stranger?" Before she could respond, I turned and disappeared back into the flow of Boston's pedestrian traffic.

Regardless of who you are — the staunchest nonbeliever or the pope himself — it was morally right to help. I do what I perceive is morally right because I place value in acting unselfishly and helping those in immediate need.

Nicholas, 20, is from Medford, Mass., and attends Tufts University. He is studying international relations and hopes to attend law school to study international law. He is a member of the Model United Nations team, and actively involved in the History Society and Alliance Linking Leaders in Education and the Services. Nicholas has interned at the United Nations Association of Greater Boston and the Edward M. Kennedy Institute for the U.S. Senate.

Plasticity helps tune our morality

By Jordan Green

In the study of neuroscience, there is a concept called "plasticity." Plasticity refers to the brain's ability to change and rewire itself — even through adulthood — through new experiences and learned skills.

I think experience can influence not just a few of the trillions of synaptic connections in the human brain, but whole people. From my own life, I can say that my morals do not come from a god, but are shaped from a conglomerate of experiences including the family in which I was brought up, places I've been, books I've read, and more.

Religious belief is not needed for morality, and the world around us proves it: Countless nonbelievers exhibit good morality through their everyday treatment of others and charitable work. Additionally, most modern theists will reject at least a few tenets of their respective religious texts (like slavery, marriage laws, cruel punishments), indicating that they have some set of morals independent of the religion that compels them to do so, even if they don't explicitly recognize it.

For all my neuroscience books and deliberative discussions and philosophy classes, I have yet to find some evidence compelling enough to merit religious belief.

I think the best thing nonbelievers can do to combat negative stereotypes about their morality is to do good, and be seen doing it. Providing positive examples of secular morality might compel others to look at nonbelievers and form new opinions — and new (synaptic) connections.

Jordan, 20, is from Reynoldsburg, Ohio, and attends the University of Arizona. She is studying for two degrees: neuroscience & cognitive science, and creative writing. She has traveled to several countries and is planning to study abroad at some point during college. She hopes to earn a graduate degree in neuroscience and have a career as a scientific researcher.

'Good Book' clearly a misnomer

By Melissa Juarez

I was an active Jehovah's Witness, better known as the person who knocks on your door at 9 a.m. on a Saturday to preach to you. My life was highly regulated by the cult-like organization, so naturally I believed everything I was taught until I actually started reading "The Good Book."

In my reading of the bible, I discovered, to my dismay, that Jehovah was the bad guy. This discovery triggered an onslaught of research on my part, which led me to discover scientific and logical impossibilities, other immoralities, and a multitude of contradictions all found in what I thought was God's perfect word.

By age 15, I realized that I was an atheist.

However, for most of my life, I was taught that religion possessed a monopoly on morality and that you couldn't be an upstanding person without God. Consequently, when I realized I was an atheist, my new mission was to find out why we are viewed as such immoral people and to truly accept that my own morals do not come from God, but from someone who is very real — me.

Although it was lack of evidence that made me select the terribly stigmatized word "atheist," I will never forget what made me start questioning: My morality clashed with the very book I was supposed to be getting my morals from. Trying to reconcile my morality with the teachings in the bible felt like trying to mix oil and water. It just couldn't be done. So, I removed the oil and now flow freely as water, thanks to freethought.

Melissa, 21, is from Madera, Calif., and attends the University of California-Fresno. She was raised as a Jehovah's Witness until she became an atheist at 15. She is seeking to become a registered nurse and then hopes to become a nurse practitioner for women's health or pediatrics.

One nation, under Voldemort

By Anne Mickey

One day during my junior year of high school, it occurred to me that standing for the daily Pledge of Allegiance went against my beliefs as an atheist because I had to pledge to the nation "under God." The next day, I continued sitting while the pledge was recited and was immediately reprimanded by my teacher.

My teacher took offense at my (non)action, believing I was being disrespectful toward U.S. troops, which was absolutely not my intention. I took the issue to the school administration, which threatened me with discipline if I continued to sit during the pledge.

When I was making my case, I asked them how they would feel if the pledge instead said "one nation, under Voldemort," referring to the villain from the Harry Potter series. My point was that they would likely feel uncomfortable standing up, putting their hands over their hearts, and pledging their allegiance to the Dark Lord Voldemort — a fictional character who's downright evil — day after day, and that this was how I felt.

In the end, I reached a compromise with my school that if I stood for the pledge for the rest of my junior year, I would be placed with a fourth-period teacher during my senior year who would allow me to sit without punishment.

So much immorality (and even amorality) has been rooted in religion that I find it ridiculous to believe that morals originate in any sort of belief in a higher power. The fact that I'm a good, kind and fair person is not in spite of my atheism; rather, it is at least partially because of my atheism.

Anne, 20, is from Scottsdale, Ariz., and attends Arizona State University. She is passionate about civil rights and many consider her a "social justice warrior." She hopes to serve in the AmeriCorps Public Allies program after graduation before having a career as an advocate for marginalized people and communities.

I don't need a god to help someone

By Chenoa Off

When I was a child, my mother had a painting on her wall of her savior; he had light hair and a crown of thorns that caused blood to drip down his face. Next to him, she had a photo of the Buddha, and on her bedside table was a little statue of the Hindu elephant god Ganesh.

In my room, I had my saviors: Charles Xavier of the X-Men, Doctor Who, Captain Jean-Luc Picard of the Starship Enterprise. With them stood their people — some women, some men, some blue, each one unique. These were my heroes, the ones showing me how to fight discrimination, to value education, to understand friendship, to cherish life and listen to my own moral compass.

My mother is a very spiritual person, and when I told her I was a nonbeliever, her eyes grew sad. She seemed to think that because I am an atheist that I could not see the astonishing beauty of our existence. On the contrary, I marvel every day at the immensity of the universe, at the complexity of living organisms.

I've seen religion bring a community together through hard times. But I have also seen religion throw my gay friend out on the streets. I have had religion tell me what decisions I cannot make for my own body. I have seen religion start fights over the name of the man in the sky. Religion is the world's greatest oppressor.

My most beloved moral is truth. I don't need a god to know hurting others is immoral. I don't need a god to know what kindness and charity is. I don't need a god to help someone.

Chenoa, 19, is from Crestone, Colo., and attends Russell Sage College. She enjoys traveling, singing jazz, skiing and river rafting. She plans to be an occupational therapist and working with special education school children.

Falling into the dogma trap

By Mackenzie Schneider

Contrary to popular belief, I am not an atheist because I'm angry with God. I don't believe in God; how can I be angry with an entity that I don't believe exists?

Also, nothing traumatic happened to me that caused me to lose faith in God. And my atheism wasn't motivated by my sexuality nor did anyone's death cause me to question God.

I considered the fact that since Christians are able to so easily dismiss every other religion in the world, I ought to be able to dismiss Christianity just as easily. So I did.

At 16, I dismissed the "necessity" of religion, and decided I would live my life how I see fit and follow the morality that I decide upon. In the years since then, I have developed a working definition of morality.

Morality for me means doing my best not to harm others and providing empathy and understanding.

The issue with religion is that it relies on dogma to maintain strength. This dogma allows hatred for people who are different to fester. It's why the Westboro Baptist Church believes that its members' behavior is moral.

However, atheists are not exempt from falling into dogma, either. I have met atheists who are so firm in their beliefs that they actively try to make theists feel like idiots.

Perhaps the first step in reversing negative stereotypes about nonbelievers is combatting our own dogma. Recognizing the value that someone's beliefs may have for them and being willing to admit that you may be wrong can help facilitate a more peaceful and tolerant environment for all.

Mackenzie, 21, is from San Antonio and attends Smith College. She is an English and philosophy double major. She has served two years on the Smith College Social Justice and Equity Committee. She enjoys painting and drawing.

Morality without hypocrisy

By Omolola Smith

The idea of a person without a god or some gods was entirely incomprehensible to me growing up in Lagos, Nigeria. Such persons were vilified by others in my society.

In 2014, Mubarak Bala was forcibly drugged and committed into a psychiatric institution in Kano, Nigeria, for expressing his lack of belief in a deity. This launched a wave of inquiry within me that no religious book or organization could answer adequately.

Later that year, I boarded my flight headed for the Home of the Free, where I would be introduced to a human right I did not know I was denied: freedom of thought.

Still, every Sunday, I found myself suspending reason for the sake of the church and its teachings, which remained an important part of my routine and identity. With each passing around of the flesh and blood of God, I knew I was being untrue to myself.

Then I said it out loud for the first time in a phone call to Kudzie, my childhood friend. "I just don't believe this sh*t," I said.

He let out his familiar bubbly laugh and confessed his own recent loss of faith. We spent the next half hour nervously laughing at each other for all the things we once believed.

When I ended the phone call, the lightness of our conversation was soon followed by an existential crisis. I spent the next week mourning the faith I had possessed my whole life.

I realized I could either give up or relearn how to exist. Within me was the hope of finding fulfillment without delusion. I looked internally for what remained after religion was taken out of the equation and found true morality without hypocrisy.

Omolola, 22, is from Lagos, Nigeria, and attends the University of Vermont. She has lived in England, South Africa, Nigeria and the United States. Omolola plans to become a civil engineer and eventually would like to pursue a doctorate in physics.

Morality attainable to all

By Katelynn Thompson

Growing up in a small town, where God is great and Jesus is the reason, it was hard to admit to atheism.

For me, atheism was less a choice than a realization. Religion is a purely cultural construct, and wields only as much power as its society allows it.

After a while, I started to refrain from mentioning my beliefs at all, dreading the expression that seems to curtain every face when the word "atheist" is mentioned. No decent, God-fearing soul wants to spend too long with a heartless nonbeliever.

To people like this, it seems that the only thing keeping humanity from depravity, crime and death itself is a centuries-old doctrine housed in a leather-bound book. They harbor the cynical belief that the only thing keeping humankind from doing wrong is a fear of retribution. Personally, I prefer being a decent person just for the sake of it, and I don't need the threat of eternal damnation to keep me out of trouble.

Perhaps it's unfair that the onus of proving morality falls to nonbelievers, but people have always disliked things that they don't understand. Therefore, it is important for atheists and nonbelievers to try to show by example that morality is not synonymous with piety.

Morality is not the watchful eye of a god weighing one's every decision on a scale of righteousness. Morality is independent from any one creed, and equally attainable to all.

Katelynn, 24, is from Hanover, Pa., and attends the University of Georgia. She is seeking her second bachelor's degree, this one in linguistics and comparative literature. Her first degree is in anthropology. She is a writer and aspiring novelist and hopes to have a career in language conservation.

Ron Reagan ad returns to ‘Rachel Maddow Show’

An ever-popular FFRF ad featuring a presidential son recently returned to premier television.

The commercial with Ron Reagan inviting viewers to join FFRF aired over several weeks on one the nation's most prominent news commentary programs, the "Rachel Maddow Show" on MSNBC.

In the 30-second spot, Reagan, the progressive son of President Ronald and Nancy Reagan, says:

"Hi, I'm Ron Reagan, an unabashed atheist, and I'm alarmed by the intrusion of religion into our secular government. That's why I'm asking you to support the Freedom From Religion Foundation, the nation's largest and most effective association of atheists and agnostics, working to keep state and church separate, just like our Founding Fathers intended. Please support the Freedom From Religion Foundation. Ron Reagan, lifelong atheist, not afraid of burning in hell."

FFRF's ad has been refused by CBS, NBC, ABC and Discovery Science. FFRF has previously been able to place it on some regional network markets, as well as on CNN and Comedy Central.

Reagan has received FFRF's Emperor Has No Clothes Award and addressed FFRF's national convention in Madison two years ago. He has publicly identified himself for years as an atheist.

The commercial has spawned a popular FFRF T-shirt, lapel pin and a soon to be announced "virtual billboard" for social media use.

FFRF advertising is made possible by kind contributions from members. Donations to FFRF are deductible for income-tax purposes.

What ‘government schools’ critics really mean by Katherine Stewart

Roots of the phrase lie not in libertarianism economics but in Confederate rebellion

This op-ed first appeared in The New York Times on July 31 and is reprinted with permission.

By Katherine Stewart

When President Trump proposed his budget for "school choice," which would cut more than $9 billion in overall education spending but put more resources into charter schools and voucher programs, he promised to take a sledgehammer to what he has called "failing government schools."

That is harsh language for the places most of us call public schools, and where nearly 90 percent of American children get their education. But in certain conservative circles, the phrase "government schools" has become as ubiquitous as it is contemptuous.

What most people probably hear in this is the unmistakable refrain of American libertarianism, for which all government is big and bad. The point of calling public schools "government schools" is to conjure the specter of pathologically inefficient, power-mad bureaucrats. Accordingly, right-wing think tanks like the Mackinac Center for Public Policy, the Heartland Institute and the Acton Institute have in recent years published screeds denouncing "the command and control mentality" of "government schools" that are "prisons for poor children." All of these have received major funding from the family of the education secretary, Betsy DeVos, either directly or via a donor group.

Friedman's legacy

The libertarian tradition is indebted, above all, to the Chicago economist Milton Friedman, who published a hugely influential 1955 paper, "The Role of Government in Education." A true believer in the power of free markets to solve all of humanity's problems, Friedman argued that "government schools" are intrinsically inefficient and unjustified. He proposed that taxpayers should give money to parents and allow them to choose where to spend education dollars in a marketplace of freely competing private providers. This is the intellectual foundation of DeVos's voucher proposals.

But the attacks on "government schools" have a much older, darker heritage. They have their roots in American slavery, Jim Crow-era segregation, anti-Catholic sentiment and a particular form of Christian fundamentalism — and those roots are still visible today.

Before the Civil War, the South was largely free of public schools. That changed during Reconstruction, and when it did, a former Confederate Army chaplain and a leader of the Southern Presbyterian Church, Robert Lewis Dabney, was not happy about it. An avid defender of the biblical "righteousness" of slavery, Dabney railed against the new public schools. In the 1870s, he inveighed against the unrighteousness of taxing his "oppressed" white brethren to provide "pretended education to the brats of black paupers." For Dabney, the root of the evil in "the Yankee theory of popular state education" was democratic government itself, which interfered with the liberty of the slaver South.

Secular culture

One of the first usages of the phrase "government schools" occurs in the work of an avid admirer of Dabney's, the Presbyterian theologian A. A. Hodge. Less concerned with black paupers than with immigrant papist hordes, Hodge decided that the problem lay with public schools' secular culture. In 1887, he published an influential essay painting "government schools" as "the most appalling enginery for the propagation of anti-Christian and atheistic unbelief, and of antisocial nihilistic ethics, individual, social and political, which this sin-rent world has ever seen."

But it would be a mistake to see this strand of critique of "government schools" as a curiosity of America's sectarian religious history. In fact, it was present at the creation of the modern conservative movement, when opponents of the New Deal welded free-market economics onto bible-based hostility to the secular-democratic state. The key figure was an enterprising Congregationalist minister, James W. Fifield Jr., who resolved during the Depression to show that Christianity itself proved "big government" was the enemy of progress.

Drawing heavily on donations from oil, chemical and automotive tycoons, Fifield was a founder of a conservative free-market organization, Spiritual Mobilization, that brought together right-wing economists and conservative religious voices — created a template for conservative think tanks. Fifield published the work of midcentury libertarian thinkers Ludwig von Mises and his disciple Murray Rothbard and set about convincing America's Protestant clergy that America was a Christian nation in which government must be kept from interfering with the expression of God's will in market economics.

'Theonomy'

Someone who found great inspiration in Fifield's work, and who contributed to his flagship publication, Faith and Freedom, was the Calvinist theologian Rousas J. Rushdoony. An admirer, too, of both Hodge and Dabney, Rushdoony began to advocate a return to "biblical" law in America, or "theonomy," in which power would rest only on a spiritual aristocracy with a direct line to God — and a clear understanding of God's libertarian economic vision.

Rushdoony took the attack on modern democratic government right to the schoolhouse door. His 1963 book, The Messianic Character of American Education, argued that the "government school" represented "primitivism" and "chaos." Public education, he said, "basically trains women to be men" and "has leveled its guns at God and family."

These were not merely abstract academic debates. The critique of "government schools" passed through a defining moment in the aftermath of the Brown v. Board of Education decision of 1954, when orders to desegregate schools in the South encountered heavy resistance from white Americans. Some districts shut down public schools altogether; others promoted private "segregation academies" for whites, often with religious programming, to be subsidized with tuition grants and voucher schemes. Dabney would surely have approved.

Many of Friedman's successors in the libertarian tradition have forgotten or distanced themselves from the midcentury moment when they formed common cause with the Christian right. As for Friedman himself, the great theoretician of vouchers, he took pains to insist that he abhorred racism and opposed race-based segregation laws — though he also opposed federal laws that prohibited discrimination.

Rearmed Christian right

Among the supporters of the Trump administration, the rhetoric of "government schools" has less to do with economic libertarianism than with religious fundamentalism. It is about the empowerment of a rearmed Christian right by the election of a man whom the Rev. Jerry Falwell Jr. calls evangelicals' "dream president." We owe the new currency of the phrase to the likes of Tony Perkins of the Family Research Council — also bankrolled in its early years by the DeVos family — who, in response to the Supreme Court's ruling allowing same-sex marriage, accused "government schools" of indoctrinating students "in immoral sexuality." Or the president of the group Liberty Counsel, Anita Staver, who couldn't even bring herself to call them "schools," preferring instead to bemoan "government indoctrination camps" that "threaten our nation's very survival."

When these people talk about "government schools," they want you to think of an alien force, and not an expression of democratic purpose. And when they say "freedom," they mean freedom from democracy itself.

Katherine Stewart is the author of The Good News Club: The Christian Right's Stealth Assault on America's Children.

This is what happens in a voucher school by Marianne Arini

A former student tells of her six dismal years in an unaccredited religious school

By Marianne Arini

Education vouchers allow parents to choose what type of school their child goes to.

Often, parents choose to send their child to a religious school, and this diverts public dollars from accredited public schools into unaccredited religious schools. My parents chose to send me to a fundamentalist Christian school from grades 7 through 12 to "protect" me from the dangers of public school.

Here's the bizarre, behind-the- scenes account of what transpired in that school and likely what occurs in many other religious schools across the country.

I attended a one-room school in the basement of our church in Brooklyn, N.Y. Our desks were lined up in one large room. The children aged 5 through 11 were kept on one side and adolescents aged 12 though 18 were on the opposite end.

Oppressive basement

Once one descended the steps into the basement, he or she was usually struck by the sheer oppressiveness of the space. There were only four windows, and they were eye level with the pavement outside, the only view being people's feet as they walked by. The fourth window was eye level with the dirt of the church graveyard.

The beige walls, linoleum floors and dropped ceilings all had a plain, worn-out look to them that wasn't enhanced by the florescent lighting. Nothing adorned the walls. Student work was never displayed, and there were no pictures or artwork of any kind exhibited.

The maximum enrollment for this school was 50 students. Most of the time, the number ranged anywhere between 35 and 45 students. We were each jailed off in our dull, brown cubicles that were partitioned on both sides, and were strictly forbidden to speak to each other.

We didn't have teachers, lessons, blackboards or dialogues about what we were learning. Instead of lessons taught by professionals trained in their subject areas, we were given five "paces," one for each subject. These paces were thin, poorly designed workbooks, created by the Southern Baptist fundamentalist fountainhead, Bob Jones University, a place famous for its sexism, racism and homophobia.

Our subjects were math, language arts, history, science and either New or Old Testament survey. Math was the only subject that bore any resemblance to the standard curriculum of public schools. In the history paces, I learned a version of American history in which the forefathers were portrayed as having exactly the same religious beliefs as present-day Christian fundamentalists, and in which the Holocaust never happened. We learned Spanish from videotapes, and the school secretary taught us typing on some old typewriters. We were taken to the public park twice per month to play volleyball as our "gym class."

Self-expression banned

That was it. There wasn't any art, creative writing, music, drama, clubs or dance. All creative self-expression was strictly forbidden. We were taught that the self, our selves, could not be trusted. We were inherently sinful from birth. Newborn babies were sinful. Since we could not trust ourselves, we should only trust God, or rather, the fundamentalist Christian idea of God. Anything that was not directly connected to their patriarchal God or their interpretation of the bible was deemed unworthy of any time, and so, the lessons in each pace, no matter what the subject, were always skewed to contain bits and pieces of religious propaganda.

We did not discuss what we learned in these paces; we were just supposed to accept it all as fact. We were handed a goal chart every Monday, which had the days of the week marked out on it. Every student was required to write down a goal of completing three to five pages in each subject per day. If we had a question about the work we were doing in our paces, we put up a tiny American flag into the hole on the top of our desk to signal that we needed to ask a question.

When the principal had a moment, he would come by, take down the flag, and try to answer the question. Most of the day was spent waiting for our flags to be answered. The principal was the only "teacher" we had, only he didn't have a teaching degree. He was a pharmacist by trade.

Once we reached a self-test in a pace, we completed it, and then were required to get up, go to the scoring table, look up the answers in the score key, and score the test. Before we could get up, we had to insert a tiny Christian flag into the hole on top of our desks. If you haven't seen a Christian flag, it's white with a blue box in the left-hand corner and a red cross inside the blue box, signifying the blood that, according to the New Testament, was drained from Jesus' body when he was crucified on the cross. The Christian flag alerted the principal that we needed his permission to get up. He would eventually come over, take our flags down, and grant us permission. If we had to use the bathroom, we had to use the Christian flag again to obtain permission.

Upon the completion of each pace, we had to take a test at the testing table, a long brown folding table. If we passed the test, we received a star to put on our personal, plastic-covered star chart, which hung inside each of our cubicles. Other than these three instances, we were not allowed to stand up and walk around. We were not allowed to leave the building at any point. We had two 15-minute breaks and a lunch break, during which we'd gather around to talk, starved for communication. At 2:30, the day was declared over — after the principal prayed.

Every day the same

Every day in Metropolitan Baptist Academy was exactly like the last. In describing one day to you, I'm really portraying seven years' worth of days that were all exactly the same. Each morning, we would go up to the sanctuary for "chapel." We would first pledge to the American flag and then turn to face the Christian flag. We would then recite:

I pledge allegiance to the Christian Flag,

And to the Savior, for whose Kingdom it stands,

One Savior, crucified, risen and coming again,

With life and liberty for all who believe.

Next, we would have to pick up the bible in front of us, lay our hand on it and say,

"I pledge allegiance to the bible, God's holy word. I will make it a lamp unto my feet and a light unto my path. I will hide its word in my heart that I might not sin against God."

After that, we'd sing "Onward Christian Soldiers," complete with all the "us vs. them" military motifs. "Onward Christian soldiers, marching as to war, with the cross of Jesus going on before!" Or, some days, it was, "The Lord's Army," with the lyrics, "I may never march in the infantry, ride with the cavalry, shoot the artillery. I may never zoom on the enemy, but I'm in the Lord's Army."

When we sang the words: "march in the infantry," we would have to march in place; ride in the Cavalry, we had to pretend we were riding a horse and bounce up and down; and "shoot the artillery," we had to pretend we were shooting off a machine gun.

After our half-hearted singing, we'd sit through a 45-minute sermon in which we were castigated for being sinful, evil creatures, all of who owed everything to God who sent his son to be murdered for us.

The church could get away with all this because the school was unaccredited. When I asked why the school didn't seek accreditation, I was told that if the school complied with an accrediting institution, it would have to change its curriculum to include evolution as a valid theory and would permit people who are not Christians and possibly homosexuals to work in the school.

Even as a 17-year-old, that sounded ridiculous to me.

When I was 17, 10 of the 13 girls in the school became pregnant, since there was no sex education and abortion was not an option because we had had it drilled into our heads that it was murder. Once those children were born, these girls went on government assistance and lived at or below the poverty line.

The vast majority of the students who attended this school remain Christian to this day. For me, witnessing the brainwashing, fear and control tactics, and the many lives ruined was enough to convince me of the great threat religious schools are to our youth, and the sanity of our country.

It's imperative that we work hard to keep the separation between church and state, and keep public money out of these religious schools.

FFRF Member Marianne Arini of Arizona teaches writing and critical thinking to college students; her writing can be found at mariannearini.com/blog.

Crankmail

Caution: Reading these unedited emails can leave you frustrated, or laughing in tears.

School prayer: Sick Nazi pigs, jesus isn't a lie and those children deserve the truth. — Alexandria L.

Church and state: Iran and other Mulim countries are run by Muslim leaders, using Koran law, so why can't this country be run by Christian leaders, using Bible law? Good Christians would not cause us to lose any political rights — like the Muslims do, so STOP trying to separate Church and State! — Steve C.

Marco Rubio: If you don't like Senator Rubio's Tweets, don't read them. Surprise, even congressmen have first amendment rights. — Jack W.

Prayer: I'm very blessed from God and all He has done for me and my family. I have 5 children that are actively serving the Lord and 11 grandchildren that will be brought up to do the same. If you don't like what the born again believer do, move out the the United States. I will be praying that y'all at ffr get saved. My heart goes out to your children missing out on the blessings of Christmas and Easter. Maybe I should sue y'all for trying to destroy America — Lorira L.

Franklin highschool: The only way you could assist me is by removing yourself from the planet. You wanna threaten to sue some highschool girls cause of a banner they made? Freedom of religion and speech thise girls are not bothering anyone. If it bothers you all that bad get hit by a fucking truck. — Christian B.

FFAF: If you want freedom from religion, that's your business: however; you and your buddy satan need to keep your split tongues, reptilian eyes, and side-nared noses to yourselves. FFAF (Freedom From atheist Foundation) — Kevin J.

YOU!: Why do you spend all your time and efforts fighting something you don't think exists?! "Every knee shall bow, and every tongue shall confess that Jesus Christ is Lord." — Phil M.

Taking our religious rights away: Close operations of your organization — Timothy F.

Remove plague at school: Atheist is crybaby..stupidity ..Lets GOD judge them ..DUH — Tena M.

Freedom OF religion: While we all sure have the freedom to believe how we want, your article almost left me speechless. How sad and unhappy you must be. So intolerable of prayer and Christianity. And your understanding of the 1st Amendment really shows your ignorance. You don't even quote it right. It says, Freedom OF Religion, not Freedom From Religion. From and of have two different meanings. And this is the LIE people have believed. And this lie has wreaked havoc in our schools; look what's going on with our youth and young adults: violence, riots, no respect for authority, and the list goes on. After trying to take Christ out of the "public square/school," look at the world around you now. I truly feel sorry for you because evidently you've never experienced the blessing that comes from serving Jesus Christ...and to know Him and His love on a personal level. — Deb E.

Alabama: I noticed your address is Wisconsin. How about keeping your comments in Wisconsin. We know our rights in Alabama. And for the record, I'm offended by your organization's purpose and mission. So according to your statements, stop pushing your beliefs on me!! — Traci R.

You and satan: Satan coms to deceive, steal, kill, and destroy. Islam comes to deceive, steal, kill, and destroy. FFRF comes to deceive, steal, kill, and destroy. Day of the Lord begins Yom Kippur in 2017. Fire comes now for one year and you will die during this upcoming year. Once you die, then comes your judgment day before the Messiah and then to the lake of fire and brimstone. The Bible brings hope and joy to millions and all you want to do is destroy it so fire comes down from Heaven in 5778 for the Millennium to begin at Sukkot 5779 (Feast of Tabernacles 2018 — John A.

LEAVE PEOPLE ALONE: Leave people alone. Stop being little whiney snowflakes. YOU are the ones taht disrespect others, not the other way around. Bunch of whiney little babies who want things just the way THEY want it and can't handle it when one teeny ounce of life doesn't go their way. Grow up. Get the hell out of town. — Jane D.

The signs in Oconomowoc: I love the signs and if you fruit cakes don't stand down. I will put up 4 more signs. Please find something worth while to do — Shawn M.

Treason!: I am declareing freedom from religion a terror group for threatening he right to freedom of religion and i am accusing freedom from religion of treason of the constitution.freedom from freligion is the enemy of the united states of america from this day forward — John B.

FFRF improves experience online for our members by Tim Nott

By Tim Nott

At FFRF, we are always looking for ways to improve our membership experience. In the August issue of Freethought Today, we unveiled the Unpleasant Companion website (unpleasantgod.ffrf.org), the first of a series of updates to FFRF's digital offerings.

This time around, we're lifting the curtain on a much bigger project that began back in the summer of 2016: our new and much-improved online membership system. The system has allowed FFRF to enhance our service to members and will also allow for the development of new features for members to enjoy.

The system went live on March 1, and we have spent the last few months getting all of our staff comfortable with the new features. Now we are ready to launch a self-serve option for making donations, renewing one's membership, and updating information, such as change of address.

To access these features and more, our members will need to login with an account username and password.

We understand that keeping track of logins for all the services our members use can be overwhelming. To ease the pain, we have tried to make the system as user-friendly as possible — and we're always open to feedback on how to make the system better! Plus, we are focused on making the login a valuable tool.

Here are some highlights:

• While FFRF has always had an option online to donate, join and renew, our new, reliable login feature makes those processes much faster and easier. No need to type in your contact information since it is already stored in the system.

• Members can also update personal information like a change of address, updates to communication preferences — including email subscriptions, and managing household members any time of day or night.

All of this also makes the organization more efficient, since less data entry means fewer typos. We pride ourselves on our extremely low administrative overhead.

In addition to what is already available, the login will be a member's pass to all-new, members-only content and features. We are hard at work building FFRF's digital future.

If you would like to help test our digital products and give feedback on products under development, send an email to This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. (WARNING: Virtual hard hat required!).

We anticipate there will be questions about the new login. As always, you can contact FFRF with membership concerns at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. or call the main office line. But, here are some Q&As members might find helpful.

• Don't I already have a login?

If you created your login on or after March 1, then yes. Logins created on the prior version of our member database did not transfer correctly as the method by which we keep your password encrypted has been upgraded.

• How do I create a new-fangled login?

Go to ffrf.org and click the "Member Login" button in the top-right portion of the screen (see image of website at the top of the article).

Click the "Forgot Password?" link to retrieve either a username or a password.

Follow the on-screen instructions to receive an email that will guide you through recovering your information.

• How do I retrieve my username and password?

Same as above. You will receive slightly different instructions based on what info you are missing.

• I'm logged in! What can I do?

There are several member information features available. One can:

• Donate, manage recurring donations, and review donation history.*

• Renew membership and update household member information.

• Update your profile information and communication preferences, including how you'd like to receive Freethought Today.

• Check on your event registration information. (That might have been helpful last month!)

• Get the email content that matters to you. (See photo below.)

* We are still transferring donation history from our previous membership database. If you notice something amiss in your history, send an email to This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Tim Nott is FFRF's digital product manager.

Government free from religion is best by Dan Barker

These are the remarks FFRF Co-President Dan Barker made to the Religion News Association convention on Sept. 7 in Nashville, Tenn. FFRF was a co-sponsor of the event.

Dan Barker

I see that Pat Boone is registered for this conference. I accompanied Pat Boone on the piano once, back in the early '70s at a huge Christian rally in Phoenix. At the time, I was an associate pastor in a California church, leading music worship and preaching. I am certain Pat Boone would never have imagined that that young man at the piano would go on to become the co-president of the largest association of freethinkers in the country, or that he would work with Richard Dawkins, Daniel Dennett and Linda LaScola to co-found The Clergy Project, which helps ministers, priests, rabbis and imams to leave the pulpit after they have abandoned belief in the supernatural. I call it "Save a Preacher."

After that rally with Pat Boone, I went on to pastor in two more churches. I was a missionary to Mexico, a cross-country evangelist, and a Christian songwriter with Manna Music, Word Music, and Gospel Light Publications, for whom I wrote vacation bible school musicals. In fact, I am still receiving royalties for some of those songs.

In 1983, after 19 years of preaching, I lost faith in faith. I threw out the bathwater and discovered there is no baby there.

Beginnings of FFRF

FFRF came into existence in the mid-'70s, initially as a result of feminism. Anne Gaylor, FFRF's principal founder, had been working for years for birth control, abortion rights and women's equality. During her activism, she noticed that the main organized opposition to women's rights was religion. The church was in league with the government, putting the brakes on progress.

So in 1976, the year of the bicentennial, Anne and her college-age daughter, Annie Laurie, formed a local group in Madison, Wis., working from their dining room table. After hundreds of people joined the group, the Freedom From Religion Foundation became a national educational nonprofit in 1978.

FFRF has two purposes: 1) to keep state and church separate, and 2) to educate the public about the views of nontheists. Not only are we people who are personally free from religion, but we also think the First Amendment mandates that our government should be free from religion.

I met Anne and Annie Laurie Gaylor on Oprah Winfrey's talk show in 1984. Annie Laurie and I were married in 1987, and in 2004, she and I were elected co-presidents of FFRF.

Today, with almost 30,000 members, FFRF has a staff of 25, including nine full-time attorneys. In the last two years alone, we have won eight lawsuits, not to mention stopping hundreds of state/church violations every year without going to court, simply by writing letters to government and school officials.

Complaints come to us

Contrary to what you may have read, we are not roaming the country looking for violations. We don't have to. The complaints come to us — thousands every year — usually from nonbelievers or people in a religious minority who are subjected to unwanted governmental religious intrusion.

We are not fighting religious freedom. We don't complain about nativity scenes in people's front yards or the Ten Commandments at a Christian school. We don't climb church steeples to remove crosses that are visible for miles.

We only sue the government. There is a difference between free speech and government speech. If the government promotes any religion, that creates an "out group." The First Amendment, which prohibits any governmental action "respecting an establishment of religion" — was written precisely to protect the minority from the "tyranny of the majority," as John Adams and James Madison put it.

Not just an 'out group'

I'm sure everyone in this room knows that the fastest-growing religious identification in the country is nonreligion. Currently, about a fourth of the nation is nonreligious, and if we look at younger people, at Millennials, one-third do not identify with religion. This is clearly not an "out group." Our nonbelief is just as precious to us as religious belief is to church-goers.

Contrary to what you might hear, we atheists and agnostics are not "wallowing in despair," leading sad, empty lives. We simply don't see any good evidence or hear any good arguments for a god.

But more important, we don't see any need for a god. In this country, there are tens of millions of good people — and around the world, it is hundreds of millions — who lead meaningful, moral, joyful, productive, hopeful, loving and charitable lives without religion. Nonbelievers are songwriters and authors. We are in the police force, the fire department and the military. We are educators and entertainers, scientists and scholars, actors and artists, reformers and revolutionaries, doctors and dancers, nurses and Nobel Prize winners, filmmakers and philosophers.

We have an annual "Nothing Fails Like Prayer" contest. In light of the Greece v. Galloway decision that allows prayer at city council meetings as long as atheists are also welcome, we encourage nonbelievers to deliver a secular invocation at governmental events that include prayer. Each year, the winner is flown to our annual convention to deliver their secular invocation to us, in person.

Current lawsuits

And that touches on one of our current federal lawsuits. Although the Supreme Court and local governments recognize that atheists can participate in solemnizing a public meeting, the U.S. House of Representatives does not. The chaplain of the House, Father Patrick Conroy, has rejected the request of Rep. Mark Pocan to invite me to deliver a secular invocation before Congress. After putting up many ad hoc roadblocks — which he has not done with other guest chaplains, and which I actually passed — Conroy finally said that the "prayers" before Congress must address a "higher power." In the draft of my invocation, which I sent to him, I point out that in the United States, there is no power higher than "We, the people."

As an officer of our secular government, Conroy's denial violates the Constitution, which declares there shall be "no religious test" for public office.

We are also suing President Trump over the executive order he signed on the National Day of Prayer, assuring religious leaders — after promising to "repeal the Johnson Amendment" — that they are now free to politick from the pulpit. As you may know, in the government's motion to dismiss our lawsuit, it admits that Trump got it wrong. His executive order does nothing, changes nothing, and actually upholds the Johnson Amendment, which most religious organizations say they like. In any event, we think all nonprofits should be treated equally by the IRS.

Which is why we are also challenging the unfair IRS code that allows "ministers of the gospel" to exclude their housing expenses from income, lowering their tax liability. When I was a minister working for a church, a religious nonprofit, I got a nice tax break. But now that I work for FFRF, a secular nonprofit, I no longer get that advantage. The government should not be picking sides.

Don't stereotype atheists

When writing about nonreligion, be careful that you do not unwittingly stereotype atheists. We sometimes see headlines such as "Atheists outraged by city prayer" or "Nonbelievers furious at nativity scene," portraying us as a bunch of angry thin-skinned malcontents whose feelings are so easily hurt. In reality, we are defending a precious American principle. When Trinity Lutheran Church sued the state of Missouri over its refusal to pay for playground equipment, did the headlines scream, "Lutherans outraged over state denial!"?

When you are looking for balance, be sure that it goes both ways. I once flew to Seattle to be a guest on a TV show to talk about atheism, and when I got to the set, I discovered that not only was the host unsympathetic, but there was also a minister, priest, and rabbi — no joke — on the stage with me, all of whom were very talkative, crowding me down to only a minute or two to make my case.

When that same show does a story about religion, do they bend over backwards to invite an atheist or secular humanist — even just one? — for "balance"? A couple of years ago, Annie Laurie went on a Fox News show to talk about one of our lawsuits, and found that she was on with three long-winded theocrats — Bill Donohue, Todd Starnes and a priest, not to mention the hostile host Sean Hannity — leaving her time to squeeze in only a quick sentence or two. That was unfair and unbalanced.

But, that is free speech in the public sphere. In the public square, however, a secular government that is free from religion is our best hope for a world with less violence and more understanding.

FFRF and U.S. govt. agree judge should ‘nullify’ housing allowance

After the Freedom From Religion Foundation's historic victory against the clergy housing tax allowance, the judge's next move is eagerly awaited. U.S. District Judge Barbara B. Crabb, who in October ruled the clergy privilege unconstitutional, now must decide how to implement her ruling.

Crabb, seated in the Western District of Wisconsin, ruled in favor of a challenge by the Freedom From Religion Foundation of 26 U.S.C. § 107(2) of the tax code, saying it demonstrates "a preference for ministers over secular employees."

In a fascinating twist, both FFRF and the government are urging Crabb to nullify this provision, rather than extend the benefits to others.

That provision, enacted in 1954 to reward "ministers of the gospel" for carrying on "a courageous fight against [a godless and anti-religious world movement]," permits churches to pay ministers with a "housing allowance." The unique allowance is not a tax deduction but an exemption, allowing clergy to subtract major portions of their salaries from taxable income.

While ruling in FFRF's favor, Crabb left open the remedy, giving FFRF, the U.S. government and religious intervenors the opportunity to file supplemental briefs.

The options include an injunction requiring the IRS to extend the benefits to FFRF Co-Presidents Dan Barker and Annie Laurie Gaylor, who have been designated a housing allowance by FFRF, or to nullify the entire statute. The IRS has denied the pair a refund based on the housing allowance designated for them by FFRF. FFRF argues that allowing clergy this benefit while denying it to similarly situated heads of a nonreligious group is discriminatory.

FFRF is asking Crabb to prospectively nullify the statute, to order the IRS to refund the plaintiffs' housing allowance and to award plaintiffs legal costs. Nullifying the law would mean that Section 107(2) could no longer be used to provide favorable tax treatment to clergy and churches.

FFRF notes that the housing allowance "constitutes an exception to the general rule of taxation," therefore an extension "would have the effect of making the exception the general rule."

David A. Hubbert, acting assistant attorney general, points out that the clergy housing allowance already costs the government about $800 million annually. If the court were to extend the tax exemption to others, the effect would be to "create a tax expenditure of unknown amount." The government noted that if the court extended the allowance, it would need to define "which secular organizations would be eligible to provide such a benefit to its employees."

Where FFRF and the government disagree is whether Barker and Gaylor are entitled to a retroactive refund.

Interestingly, the government indicated it is "still considering whether to appeal the court's final judgment in this case." The government asks to stay all relief pending appeal, which FFRF does not object to. However, FFRF opposes the government's request to stay the court's judgment for a whopping 180 days after the final resolution of all appeals.

Needless to say, FFRF opposes the religious intervenor's request to remand the case to the IRS to give "the IRS or Congress an opportunity to the court's ruling."

This is FFRF's second time in front of Crabb over this particular inequity in the tax code. Crabb ruled in FFRF's favor in 2014, creating near hysteria by the clerical press. The 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, however, ruled that Gaylor and Barker lacked standing to sue because they had failed to apply for a refund.

Accordingly, the couple, who are married, applied for a refund and went back to court after being denied one by the IRS. Also a plaintiff is Ian Gaylor, representing the estate of Anne Nicol Gaylor, whose retirement as president emerita was in part designated by FFRF as a "housing allowance." She had requested a refund, but was denied it during her lifetime.

FFRF eagerly anticipates the judge's subsequent step.

The case is Gaylor vs. Mnuchin, 16-cv-215-bbc. FFRF is represented by attorney Richard L. Bolton.

For Veterans Day, honor all vets — including atheists in foxholes

The Freedom From Religion Foundation urges that "atheists in foxholes" and other freethinkers who have served our country be honored and remembered this Veterans Day.

It's unfortunate that during World War II, journalist Ernie Pyle promoted the myth that "there are no atheists in foxholes" — a falsehood that endures till today.

A quarter of FFRF's membership are veterans, and a quarter of active duty military identify as nonreligious. Yet members of the military are often subjected to overt proselytization by religious superiors and tax-paid chaplains. And all too often, a Christian cross is put up on governmental property and dubbed a "war memorial." Courts have repeatedly ruled that Christian crosses, the pre-eminent symbol of Christianity, may not be placed on public property. A Christian cross on public land establishes Christianity as a state religion, giving it preferred status and endorsement. But when such an unconstitutional cross is excused as a war memorial, it sends an ugly and discriminatory message of exclusion, signaling that only Christian veterans are worthy of being honored.

That's one reason why FFRF has erected two monuments to atheists in foxholes and other nonreligious veterans. One sits in a piney woods near Lake Hypatia, Ala., lovingly carved by the late Bill Teague, who served in World War II.

The other impressive monument, made of the same granite as Mount Rushmore, resides in FFRF's Rose Zerwick Memorial Courtyard and Patio outside Freethought Hall, FFRF's bustling office building in downtown Madison, Wis. (Both monuments are pictured here.)

The genesis of these unique monuments was the decades-long court challenge to remove a 43-foot Christian cross from atop Mount Soledad in La Jolla, Calif. Although it was claimed after-the-fact to be a veterans memorial, it was known as the Easter cross and stemmed from a tradition dating to the 1920s, when the Ku Klux Klan burnt crosses in the then "exclusive" neighborhood. A lawsuit, the longest state/church court battle ever, was begun in 1989 by veteran Phil Paulson, who received FFRF's first Atheist in Foxhole Award. After Paulson died, possibly of cancer caused by exposure to Agent Orange during the Vietnam War, FFRF State Representative and veteran Steve Trunk took up the cudgel. Steve also was named an Atheist in a Foxhole. That case finally ended the past year. Following numerous interventions by religionists and Congress, it was resolved rather unsatisfactorily, with the land and cross being sold to a group established to "save the cross." But at least all the courts conceded that the government could not continue erecting that cross.

At one point in the long and convoluted court battle, officials offered to put the land under the cross up for bid. FFRF's feisty founder Anne Nicol Gaylor immediately proposed replacing the sectarian symbol with a monument to "Atheists in Foxholes." Needless to say, FFRF's bid was not accepted. But Patricia Cleveland, the "veteran" leader of FFRF chapter Alabama Freethought Association invited Anne and FFRF to create and place the first monument in the world honoring nonbelieving veterans at the Lake Hypatia Freethought Advance ("not retreat"). And so a little freethought history was made. FFRF added a monument at its national headquarters in Madison, Wis., in 2015 during our building expansion.

Veterans, their families and active duty freethinkers are most cordially invited to visit and contemplate FFRF's monument honoring them and their service.

The words, penned by Anne, read:

In Memory of

Atheists in Foxholes

And the countless freethinkers who have served this country with honor and distinction.

Presented by the Freedom From Religion Foundation with hope that in the future humankind may learn to avoid all war.

FFRF nemesis Roy Moore accused of sexual misconduct with minors

Another inveterate enemy of state-church separation has been accused of sexual abuse.

In an explosive article, the Washington Post details the story of four women who accuse Roy Moore of having inappropriate sexual conduct with them while they were in their teens and he was in his 30s. Moore is currently a candidate for the U.S. Senate seat from Alabama that Jeff Sessions vacated to be attorney general.

Moore is the disgraced former judge who was dismissed from his position on the Alabama Supreme Court for refusing to comply with and uphold the Constitution — twice. FFRF has long fought with Moore, even before he placed, and refused to remove, a two-ton granite Ten Commandments in the Alabama Supreme Court building. FFRF's Alabama chapter, the Alabama Freethought Association, sued Moore in 1995. Moore was a county judge in Gadsden, and he forced jurors to pray and displayed his handcrafted wooden Ten Commandments plaque above his bench.

The Post article details sexual misconduct that took place from 1979 through 1981. The stories of the four women share some similarities: an older man plying teenagers with alcohol, taking the girls on "dates," and even using the prestige of his office to cultivate the relationships.

Moore's infamy is tied to his willingness to abuse his public office to promote his personal religion. His primary loyalty as a judge was not to the law and the Constitution, but to his bible. The women's stories reiterate Moore's shocking disregard for public service and public office. He used his position as a district attorney to gain the trust of Nancy Wells, mother to then 14-year-old Leigh Corfman. Waiting outside a courtroom on a wooden bench, Moore approached the mother and daughter according to their retelling. Moore, whose office was down the hall, explained to the mother that she didn't want her daughter to go into a child custody hearing, and that he, a district attorney, would watch the child. Then:

Alone with Corfman, Moore chatted with her and asked for her phone number, she says. Days later, she says, he picked her up around the corner from her house in Gadsden, drove her about 30 minutes to his home in the woods, told her how pretty she was and kissed her. On a second visit, she says, he took off her shirt and pants and removed his clothes. He touched her over her bra and underpants, she says, and guided her hand to touch him over his underwear.

Moore also used his office to get near and select another victim, Debbie Wesson Gibson, who was 17 when Moore spoke to her high school civics class.

Moore has denied the allegations the four women are making independently of one another.

Moore's public displays of piety will no doubt be called hypocritical, but while he is certainly a monster in many respects, Moore's alleged sexual assaults didn't violate any of his cherished commandments. There is no prohibition of rape or child molestation in the Ten Commandments. Neither even rates mention in the supposedly highest moral law Judeo-Christianity has to offer. There is no consent requirement for sex. Even in the rest of the bible, rape is not treated as a crime against a woman, but as a crime against the man who owns the woman.